Exploring the Evolution of a Lost Shot From Script to Screen

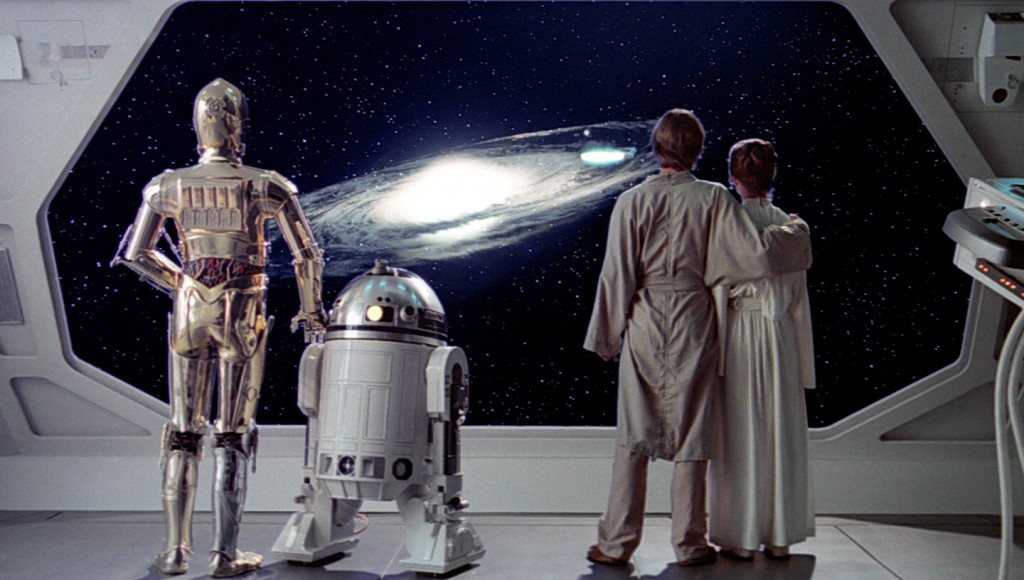

[Image from the Empire Strikes Back Blu-ray. Color correction emphasizes blue spill that was normally lost to viewer.]

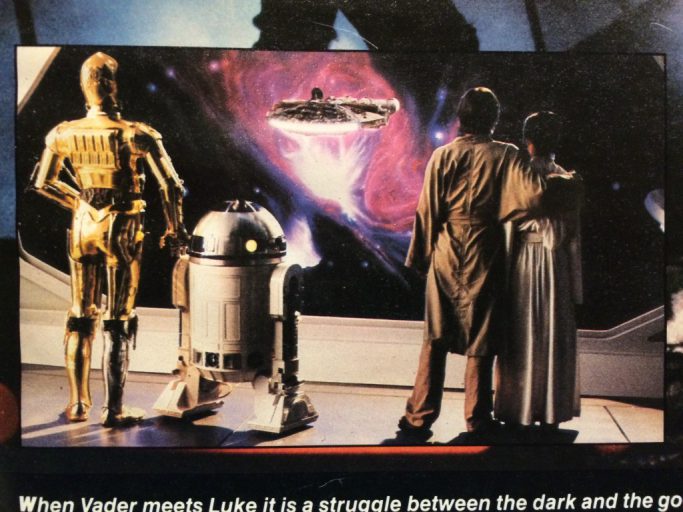

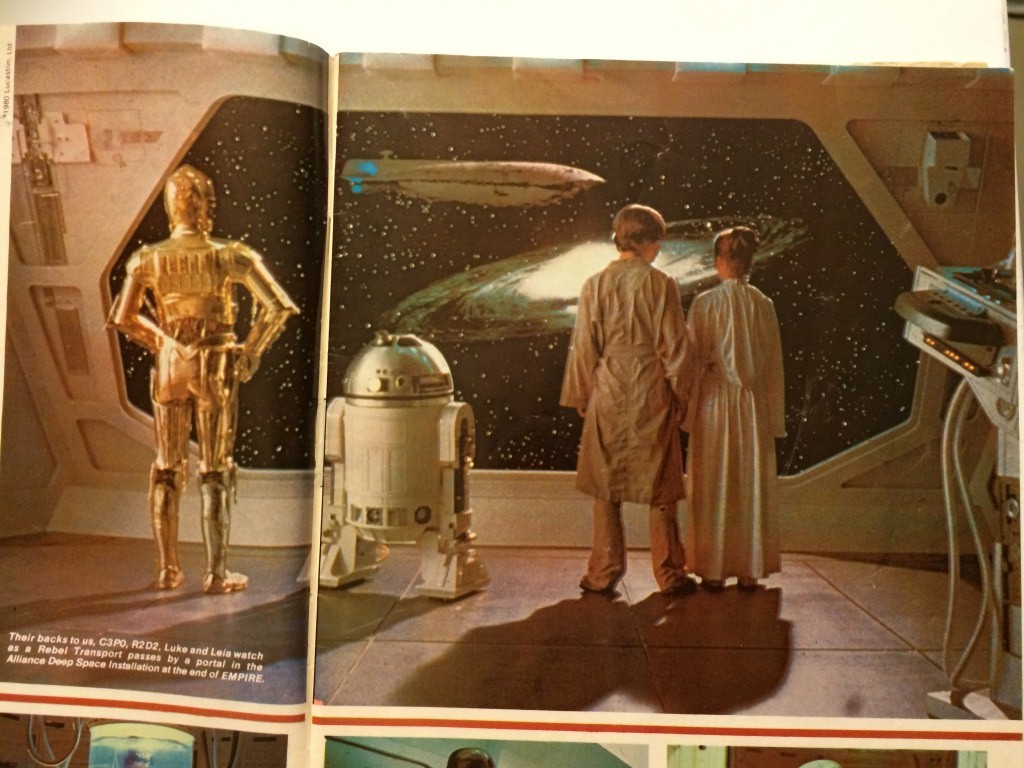

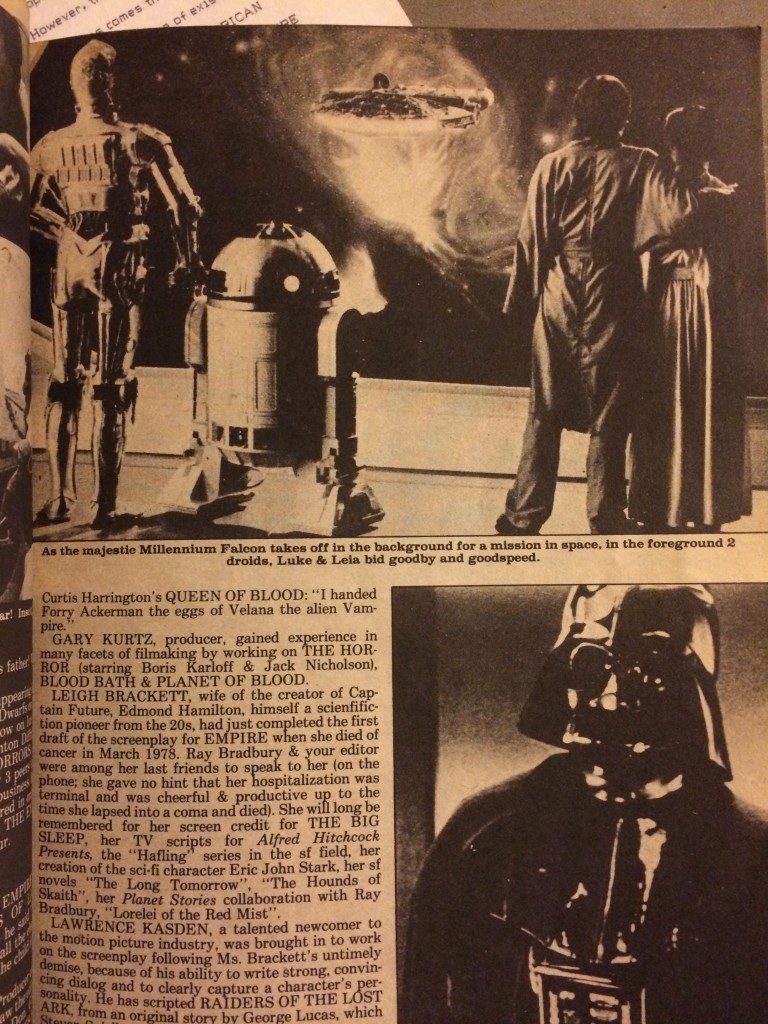

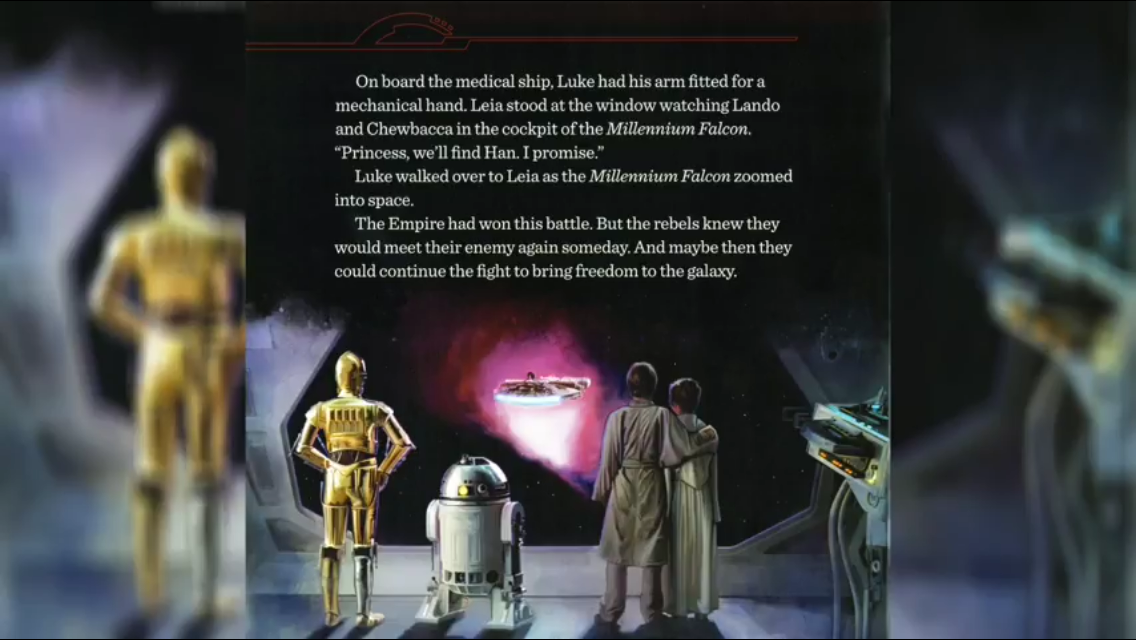

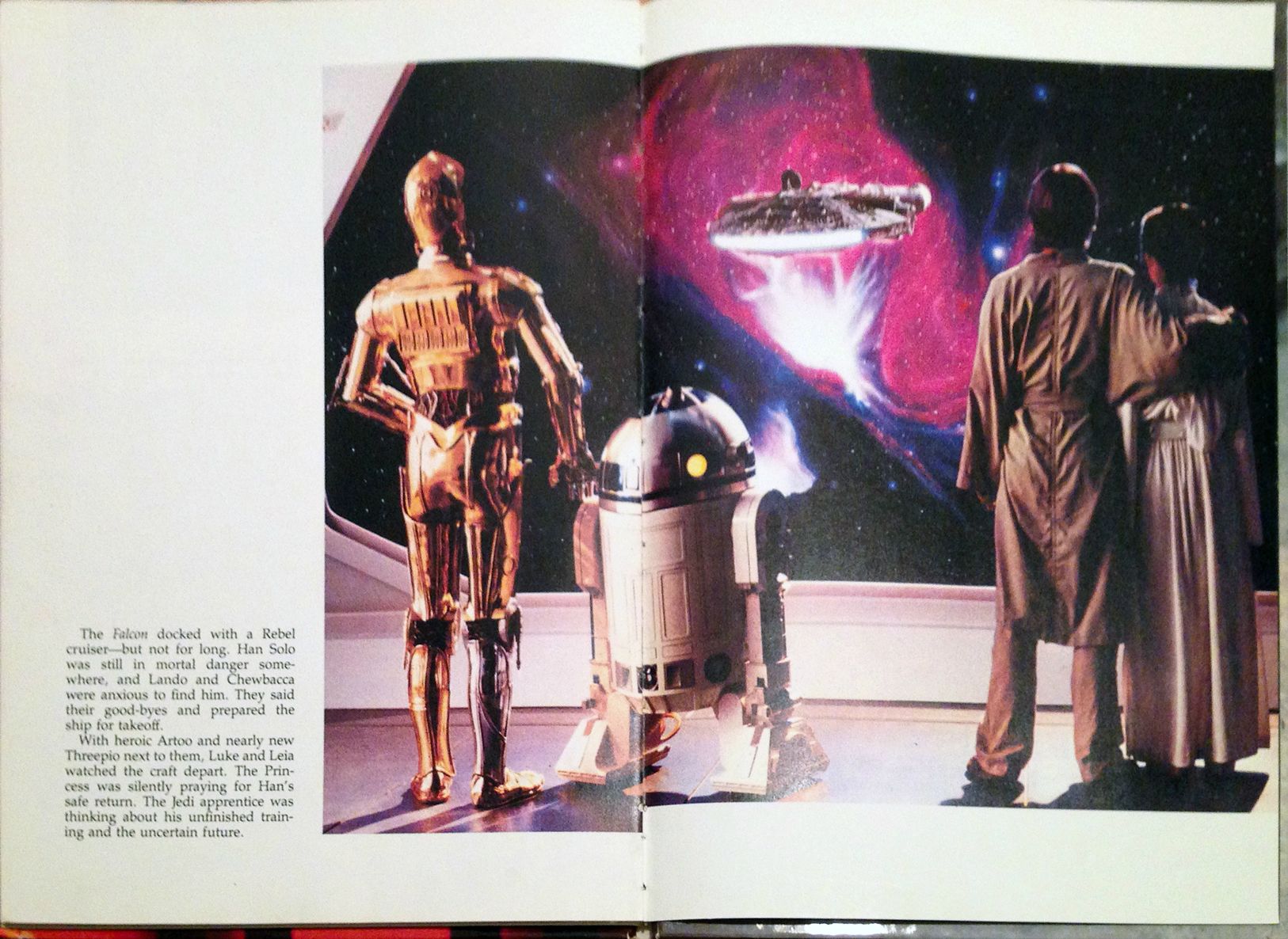

The near final shot of The Empire Strikes Back (TESB) of the Millenium Falcon flying off into the sunset — or rather the ten thousand sunsets of a spiral galaxy — is one of the most iconic, and oft-printed promotional images from the film. Due to the amount of time it takes to preduce the material to coincide with the film release, magazines, album covers, and posters must start as soon as pictures are ready, whatever their condition. In this crossover realm, before the film is actually finished, while concepts are still evolving, the iconic shot we all know and love from the end of the film is different — Very different.

One is left wondering where this particular interpretation of the final shot came from? Looking through the JW Rinzler book about The making of TESB, where there are quite a few never before seen images, it would seem the most logical choice to find the picture, as the book is an exhaustive search of the Lucasfilm archives. However, the photo I remembered vividly seeing as a youngster was surprisingly missing in the book, nor was there any information referring to it. The Rinzler hardcover was quite thorough, showing behind the scenes shots, posters, marketing materials, and other related promotionals, yet that image, which was included in the the Empire Strikes Back soundtrack booklet was nowhere to be found.

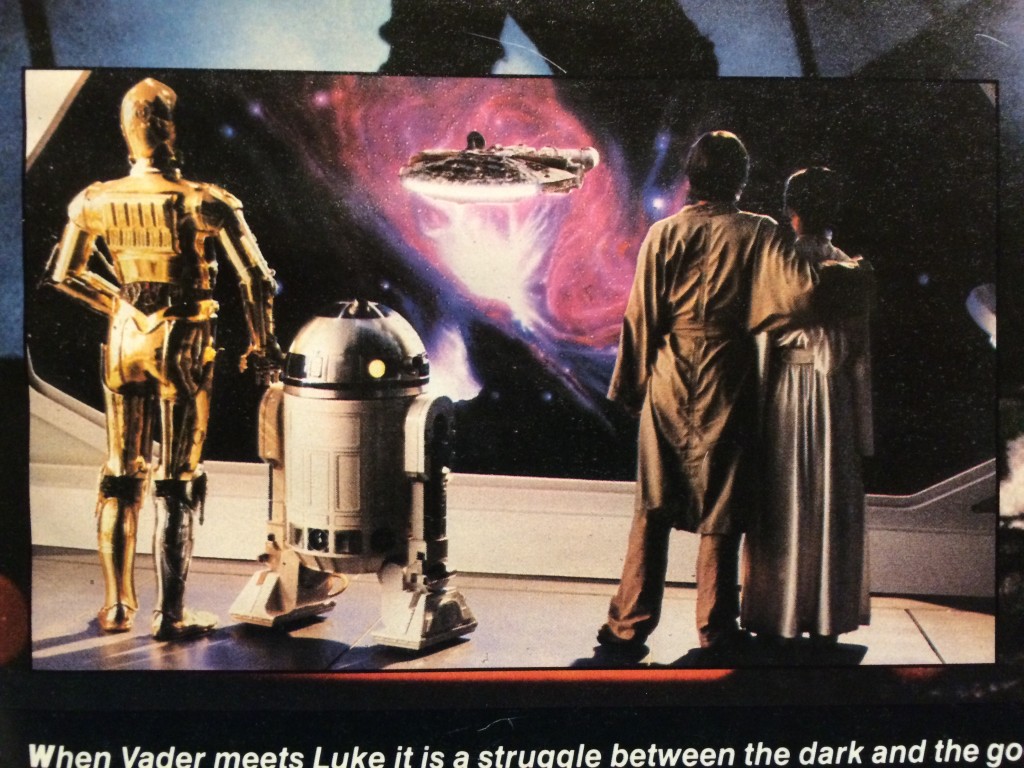

What a profoundly different look to the finale! Maybe it was just an early mockup that only showed up this one time, but after thirty years, it is curious that no one has mentioned it — not once. I immediately went to my vast collection of Starlog, Fangoria, Fantastic Films, and finally Famous Monsters magazines to further my research, and found the image reproduced at least one more time in black and white. Further internet searches reveal that the same layout also appeared in TESB storybook pages, and confusingly BOTH versions later graced the Special Edition reprint of that book. At first glance one would consider that this is a promotional image, merely painted before the film was complete to give magazines something to write about, but one reality of the VFX process of the day may dispel that notion, advancing the theory that it is a lost shot — it is fully composited with the background painting and miniatures.

[Several Print Magazine examples from the era shown below. Click to enlarge the gallery.]

In all of the other promotional material for the film, any shot with actors in it from an angle in the final film is rarely an airbrushed photo montage. It is more often a frame of film that journeyed through the myriad compositing processes used at Industrial Light and Magic. This particular image is a blue screen composite, requiring special filters, and film processing steps to separate the background. There was no Photoshop in those days, so doing this full composite by hand would require extremely delicate X-acto blade and airbrush skills to precisely fit that edge. All indications, such as the soft edges, and detail, are that this sequence went through the full composite process, and is not a montage paste-up.

It is not unusual for filmmakers to change their mind, and a concept once thought solid, may soon be nothing more than the next idea thrown out for some other dramatic purpose. So many great scenes on the cutting room floor — which are generally the fodder for DVD extras. This composite admittedly contains a very saturated color palette, and the Millenium Falcon literally flying into a vibrant sunset in space may have been too gaudy of an image for the film’s melancholy finale. Really no need to get into the nitty gritty of those small decisions (after all Luke Skywalker was female in earlier scripts, and it took over 40 years to resolve that issue and isn’t that a much juicer topic few speak of?). As for this lost shot, there is still not a DVD extra to see.

The big question to explore is, what clues exist about the big red nebula, why it existed, and what other possible visuals were planned for the ending of the film back in 1978-1980? Let’s look at the evolution as best we can with existing sources.

The Hunt Begins

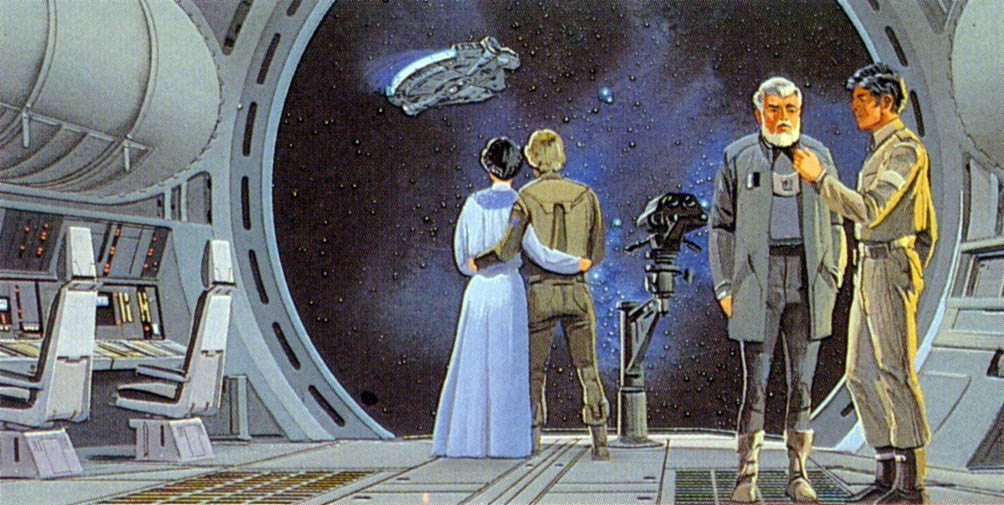

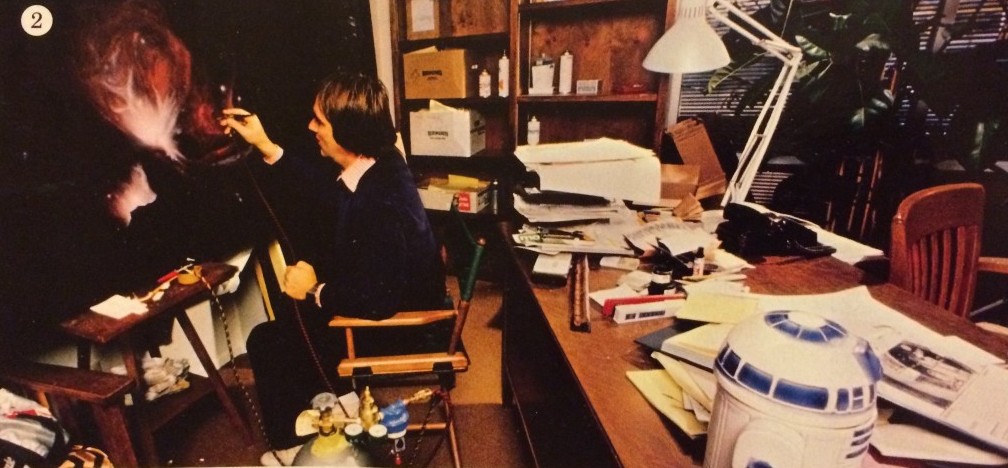

Examining every storyboard, and every sentence from the production notes in every book of Star Wars magic in my library took some time. There is no surety where each of these exist in the timeline, but we can reconstruct a plausible one by examining the clues extant. George Lucas relied on production paintings of key moments in his films to communicate dramatic intent to his team. One of the early production paintings by Ralph McQuarrie depicts the scene. It is obvious in this early draft that Luke and Leia are in each other’s arms, and watching the Falcon fly away. It is likely at this point is that it was Han Solo flying with Chewbacca on some other unnamed adventure, as I do not think Lucas had fully realized a story with Carbonite Encased Han until later.

McQuarrie would often revise his paintings as designs evolved over the course of the production. The next version shows a more complex star background behind Luke and Leia, and yet one more iteration starts to introduce other characters into the final scene (ostensibly medical doctors) and a slightly more complex nebula in the background.

McQuarrie painted many version of this scene as it evolved, it would seem.

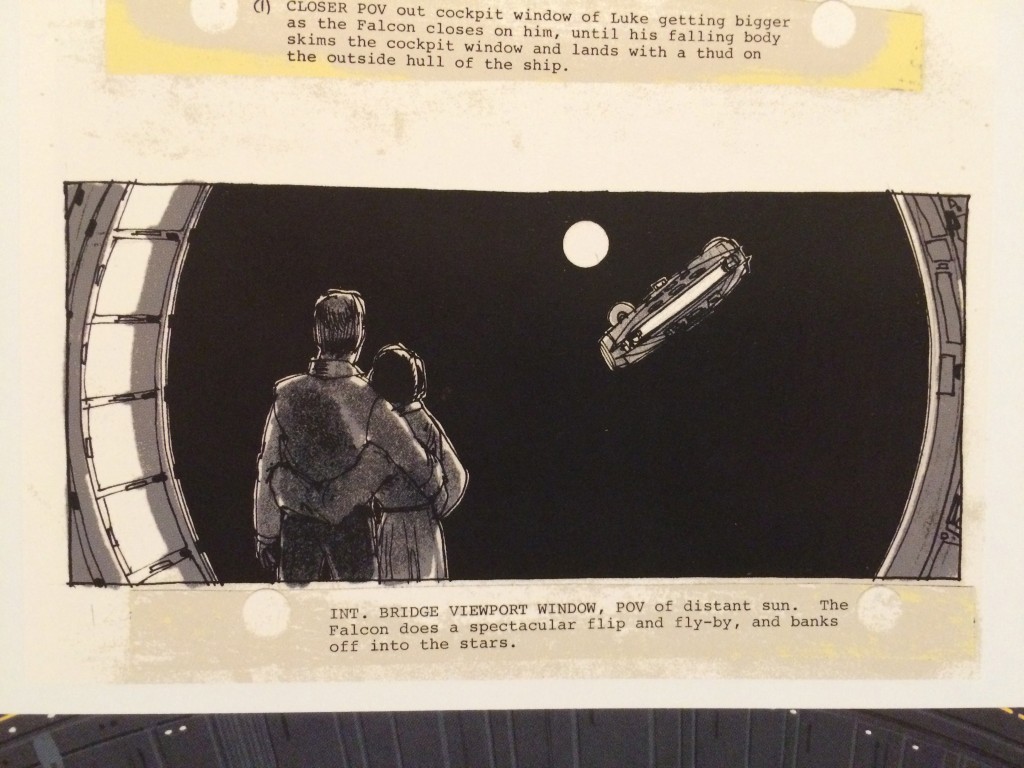

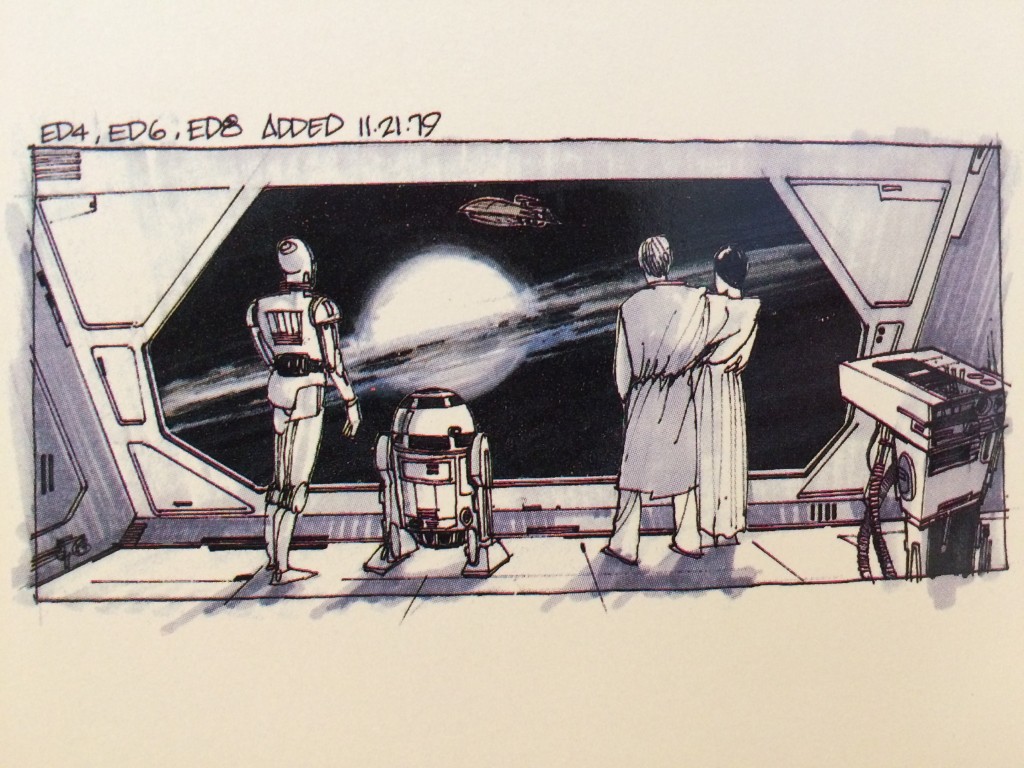

The next image I found of the departure sequence is a storyboard very similar to the first McQuarrie painting with a singular sun drawn in the middle of the frame, and still using the circular window. The Falcon is riding into the sunset. A very simple, small sunset.

Leigh Brackett and Lawrence Kasdan’s fourth and fifth draft of the screenplay explains the evolving concept in this manner:

"[Fourth Draft]. INT BRIDGE - STAR CRUISER - VIEW PORT - POV - SPACE POV of distant sun. The Falcon does a spectacular flip and fly- by, and banks off into the stars." 10-24-1978

"[Fifth Draft] Leia walks to the big round window, in the background a large red star is outside the window past the hull of theship with one small planet." 2-20-1979

These script entries provide a little inspiration for the red color scheme for sure, and obviously departing from the look dictated by the McQuarrie paintings. This detail of the red sun is missing in official versions of the final shooting script, which more closely adhere to the Spinning Galaxy image produced in the final film. But at this point we have two influences that begin to suggest the direction in the missing shot.

Building The Effect

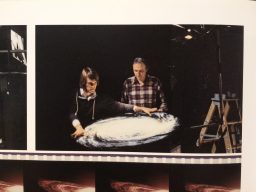

There are several photographs in multiple books showing how the final spinning Galaxy was created.

The basis is a flat black turntable, littered with [salt] crystals to simulate stars. This was slowly turned while the camera ran to provide movement and interest to the image, despite what the actual physics that implies on a stellar scale (this is a movie, so no need to tear apart the physics of it too much). This effect was reproduced in the same manner for the recent Star Tours ride updates at Disneyland.

Of particular note is that in the margins of the book, in the making of TESB it labels the spinning Galaxy as a nebula. Since nebula are generally gaseous remains of dead stars, and often act as stellar nursuries, there is likely to be a smattering of stars inside them — but the use of salt crystals infers millions of them. Definitely a galaxy in appearance, and the resulting printed nomenclature and speed of movement has many well intentioned Star Wars analysts describing it as another form of nebula. It is more likely, in the world of Special Visual Effects, that this particular use of the word “nebula” — a reference probably told to the author of the book by the artists who made it — was a holdover from the abandoned shot design. The teams had worked on it for so long by that name (and I assume the element call sheets still labeled it as a nebula) that it was incorrectly referred to as such in the text.

My final discovery during this research project also came from my magazine library. An old copy of National Geographic World magazine had a section on the special effects of The Empire Strikes Back. I tore through it in the 1980s, examining every nuance of the images for clues on making my own special effects. I recalled one such picture, henceforth found in this magazine: Special Visual Effects co-Supervisor Brian Johnson (just off his Oscar win for Alien) armed with an airbrush painting a spectacular, red nebula. A nebula seen in the lost ending of The Empire Strikes Back. Were this a promotional paste-up, or airbrushed frame, it would have been painted over a photo printout of the negative, not as its own element. Johnson is clearly posed at this image as a full size matte painting. Owing to the nature of promotional photographs, we can only assume he is the actual artist with only this as proof, as scant information exists anywhere else at this time, and he had other duties on the film. But if the shot in the magazines is just a promotional photo, it was an expensive one for sure. This could be nothing more than a posed photo, and we have no way of knowing without more information.

Some of the magazine sources from my library for this article:

Off Into The Sunset

To hazard a conclusion, it is likely that this image is far from a mere promotional mock up, all the evidence points to an actual direction the final film was headed toward. Whether the original negative exists anymore is anyone’s guess. It is almost the Lucasfilm archive equivalent of looking for king Tut. There are a few heresay accounts from artists who worked on the film that confirm that upon seeing it, Lucas reconsidered the approach, and directed the ending we now have, and there may even be a textual hint from the time that alludes to that.

Star Wars Aficionado explains some changes in the script and filming:

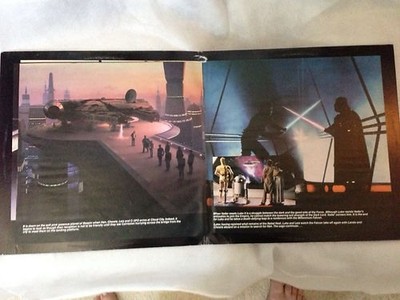

During that original July filming, Anthony Daniels was keenly aware that the final scene, in whatever scripted/storyboarded form it was in, might not prove satisfying to audiences when cut together, and vocally expressed his opinion that the sequence would need to be re-shot. His instincts would prove right, as new storyboards were drafted by ILM's Nilo Rodis-Jamero on 21st November 1979 (and listed as "added" shots) for filming of the interior scene, presumably done later that month (in the US (ILM) or at ELSTREE?) or into December 1979 with Carrie Fisher, Mark Hamill, Anthony Daniels, Kenny Baker and the robot controlled Artoo.

From the clues we have, it seems George Lucas did take pause, and rethink the ending to his film. It was very important to hit the right tone, in a show with a cliffhanger ending. Despite these few photos being the ONLY reference to it, in my opinion George made the proper decision. At the very least this lost ending is an exploration of the creative process. A demonstration that every idea does not come out of someone’s mind fully formed, but evolves to create a reality that we will pay money to see in a theater, DVD, or digital download — over, and over again.

The mystery remains unsolved.

[editors note] After this article was posted, Lucasfilm put out a new book reprinting the original storybooks. The mystery is handed down.

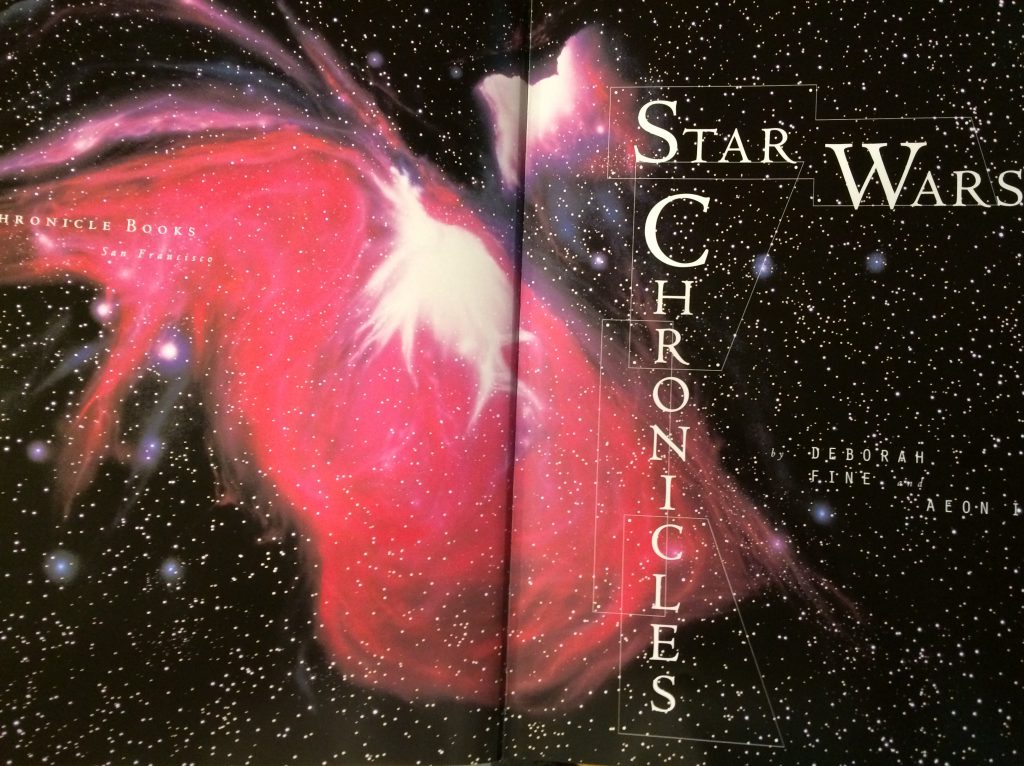

A late breaking discovery from the inside cover of The Star Wars Chronicles Book — inferring that this painting still sits in an archive somewhere.

-AG

About VFX Archaeology:

This article is part of an interesting trend with the Star Wars movies on many different Internet sites, books, and chat rooms. This is almost an archeological dig, trying to piece together lost stories from the films, or artifacts of the production that no longer exist. To some degree that is true of many landmark motion pictures, but the Star Wars saga has so profoundly changed the filmmaking process, and the way visual stories are told, that there is always great interest at exploring the crossroad. They are a good launching point to dig from. It’s the equivalent of discovering steel swords hundreds of years out-of-time for filmmaking historians. It is an attempt to grasp the serendipity that produced the magic that is Star Wars. It may be easier to contact the original artists and ask them, but exploring with only what you have can be far more educational.

THANK YOU for this-

I always remembered the nebula- swore I saw it in the film (maybe not)- and always wondered why they changed it from the nebula to the less likely galaxy. Appreciate this.

The fact that the image is composited doesn’t mean it’s not a promotional photo. There are numerous other photos like this from these films that are meant to represent scenes from the movie that are fully composited images. There would have to be because part of what’s being sold to the audience are the effects. And so you get shots like what appeared in the 1980 storybook (approaching AT-ATs, Falcon being chased by the Star Destroyer) that represent those scenes from the movie but aren’t literal shots in the movie.

The red nebula was very likely chosen specifically for the needs of this one photo and not necessarily because they changed their minds about the shot for the movie itself (although we can’t completely discount it). In the movie the grey-ish white Falcon is moving against the white nebula. At 24 frames a second, you can clearly discern one set against the other. In a still frame that becomes a little tougher. The Falcon is strategically placed in the promo photo that gives a better view of the ship than you would otherwise get from any one of the actual frames from the movie.

They didn’t have Photoshop then, but they did have the ability to photograph individual elements using reversal film stock (aka slide film). Black areas are transparent on such stock as it’s designed to be projected. All you have to do is photograph your individual components against a black backdrop, then take the pieces, line them up, and rephotograph the final image.

There would of course be some expense involved in it but promoting movies is expensive but it’s a necessary expense.