Scribbling is the Universal Language.

If a picture is worth a thousand words, it is likely that two thousand words will be required to properly describe how to correct a problem in a stereo 3D converted image. I have seen the notes go on for pages (dictated some of them myself, after all) describing how a character’s foot is too deep in 3D space, compared to its surrounding features, and sinking into the ground.

If you have ever sat in a screening room with several supervisors, they all see the same problem a different way. It is often quite entertaining to see Academy Award winning supervisors dance as they pantomime the problem, or realize how ridiculous you look as you do the same dance later for another shot — someone else is greatly amused — but at least you and the supervisor are seeing the same problem. Invariably there is some poor soul who rarely ventures an opinion, writing down everything that is said. There must be notes, of course, and one hopes they make sense after all of this theatrical performance. When the problem shows up the next day the supervisor dance returns, as they once again try to describe with words what they are seeing.

Of course there are supervisors and clients who may have a complicated day before they arrived at the screening. They leave very short, profanity-laden instructions about the obvious abortion they just saw, and wonder why they are paying the obviously blind artists they hired. Generally these notes are written down, but rarely sent to the artist.

What do you write down? What is the content of the message? It is important for the supervisors to collect all these notes into as cogent a thought as possible, and deliver clear instruction to the artist. However, since we are working with images, we quickly devolve into speaking of pixels, blurs, what procedures we would take if the project was on our computer, and the other language used over the past few decades for Visual Effects. “Move this two pixels to the left” is a valid comment for better composition, but two pixels could be the one thing that breaks something else in a stereo frame, or related elements in a composite. Since we are not neck deep in the elements of the shot, our direction could be false at this granular level.

In standard VFX work, during video chat sessions it is common to draw on the frame with special tools for clarity. Yet, even when we draw on a frame, the information displayed is unique to each person who creates it. I actually received an important reference for correction from one of these sessions that only had a single arrow drawn on it. Now I needed three pages of text describing the problem. With everyone communicating in the room at the time, the single arrow made perfect sense, I am sure, but it clarified nothing.

The artist is very often confused. Add to that fact that your native language may not be the first language your artist speaks, if at all, the pages of notes must go through one more step of interpretation. Ever play the telephone game where one person whispers something to another person, as they keep passing it on until the message is lost in translation? It can be a lot like that. Furthermore, local cultural references (like the telephone game) are many times lost on those who are not of your culture. The confusion continues to grow.

Mark It Up

Let’s cut to the chase, instead of describe the problem any more. Pictures communicate more information. A single drawing can inform so much better than words can, as long as we speak the same language — and we are not referring to English — thus we must use pictures so as to minimize exposition. We need a common visual language to draw on a stereo3D frame that clearly communicates the intent.

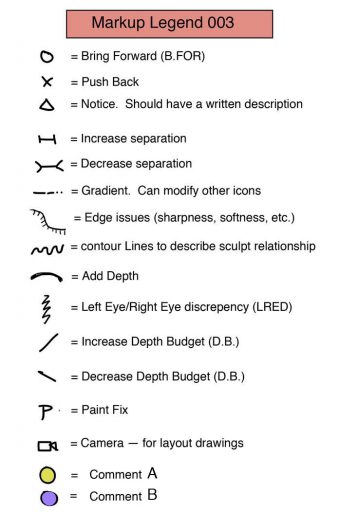

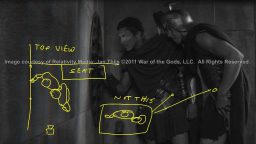

The challenge to a conversion artist is to re-engineer the image stereo with only perspective as reference, so we must always talk about depth. Any image mark-up is not merely about fixing a matte line, or circling a feature, the communication must speak to what they are actually doing — as mentioned in an earlier post on Why Dimensionalization is Bad, what the artist is doing is called Depth-Sculpting. While designing a common iconography, it is necessary to design it to communicate sculptural information, in perspective.

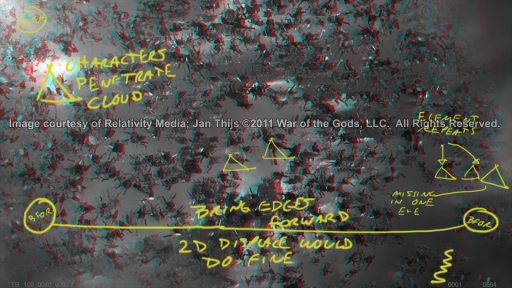

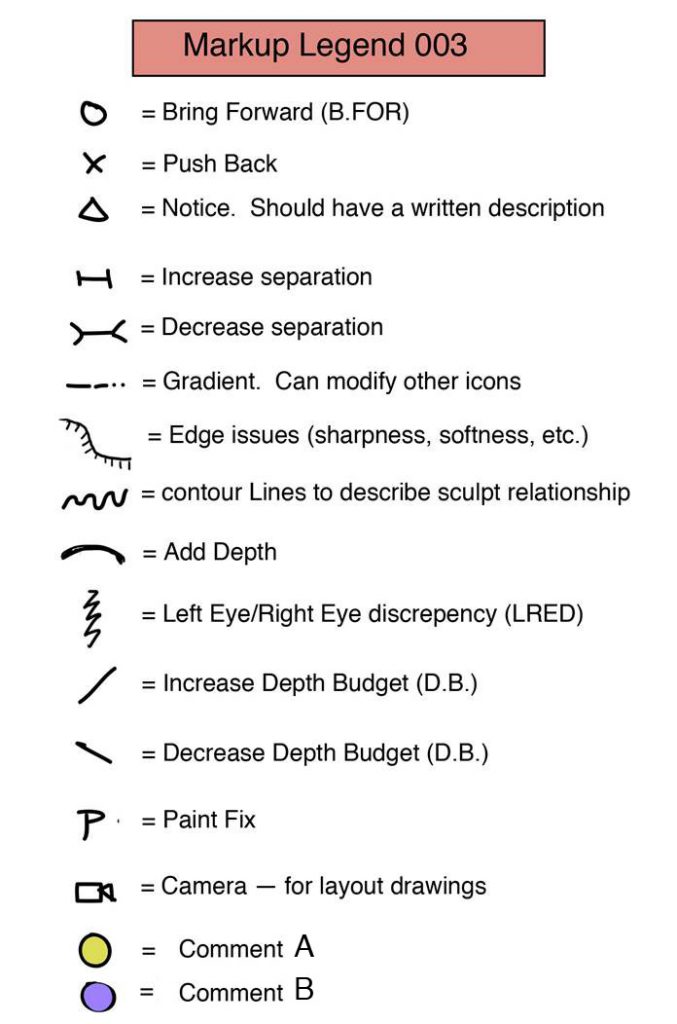

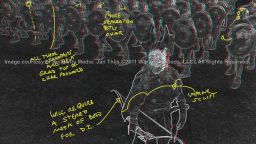

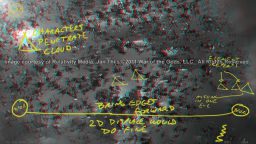

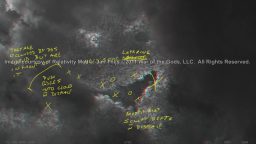

During the production of Immortals in 2011, such a markup language was put together, and sent to various vendors, by which most of the notes were exchanged on marked-up anaglyph frames. Drawing on anaglyph movies with a standardized stereo markup language, with two colors that are “anaglyph safe,” allowed both the Stereographer, and his assistant (a euphemism for myself) to mark areas of concern in a stereo 3D image, and suggest corrective action. The marked-up frames were then exported. Visual Effects vendors and conversion vendors adjusted the images as necessary, quickly understanding most instructions despite language barriers. The still images replaced paragraphs describing a problem, and were easily transmitted via encrypted files or secure FTP.

As you can see from some of the examples here, icons representing depth direction, and pictograms are most often used, with some written information on occasion. The pictograms are clean ways to describe relationships in the frame without limitation to the perspective of the shot. Although the written portions violate the concept of merely a drawing, it helps tie a note directly to the picture instead of a disassociated page of notes. If an image comes back so heavily marked up that you can barely see it, the artist instantly knows he missed the mark, and does not have to do a lot of reading.

The more time we can save clearly communicating, the better the product will be, and the money will hopefully be on the screen. Although the markup language was not implemented directly with all vendors during the production of Immortals, its use did reduce the numbers of iterations of a shot, and improve the quality of the final result. It improved communication across language barriers, and produced better results sooner.

Conclusion

Due to growing global stereo 3D production, it is necessary to communicate artistic intent, or corrective action that is outside the boundaries of the written word to artists. The world does not speak a common language, and words do not always clearly define a visual issue, especially when virtually sculpting a stereo image. Improved methods using common iconography provide a more direct, and denser amount of information quickly.

This production proven system communicates stereo correction to artists with standardized icons on anaglyph images. It is intended to be adopted, and improved industry-wide. Please pass it on.

AG

Lovely work. However, I find great creativity in trying to describe the problems with words as well. It’s my preference in part because pulling up notes that someone can read to me while I’m looking at an image is easier than finding a picture and changing my focus to interpret what was said with the previous submission. Both toolsets are useful though the visual one clearly has an advantage when working globally.

There will always be written instructions, due to the nature of the screening room, and this is not intended as a full replacement. The sketch-based system proposed here is the beginning of standard iconography. I encourage everyone to pass it on, as there are already artists and companies using the system in production.

AG