Information and title updated 03/20/2014

I was there at the end.

Richard Edlund’s BOSS film studios (named after his favorite shotgun, but originally BOSS FILM CORPORATION **) was a powerhouse of creativity. It followed in the tradition set by Doug Trumbull’s Entertainment Effects Group, which Edlund purchased to form BOSS when he left Industrial Light and Magic: 65mm image acquisition and compositing. On the heels of the visual effects revival, Edlund and his team produced two benchmarks of visual effects, namely 2010: The Year We Make Contact, and Ghostbusters.

To this day I am enamored of 2010 by the camera work of Dave Stewart, miniatures by Mark Stetson, and ground breaking compositing by Mark Vargo (and all their respective teams) – on par with the work 15 years earlier on the original 2001 A Space Odyssey. It is also one of the first uses of a computer generated planet, to depict the turbulence of Jupiter – outsourced to another company and combined in optical at BOSS. Along with Die Hard, 2010 is one of the penultimate examples of optical compositing to this day.

So many good films crossed the threshold of BOSS in Marina del Rey, CA, and a few not-so-good, but there was always a spirit of innovation and creativity driving them, despite the variations of budget. The ZAP (Zoom Aerial Printer), and motion control cameras were wonders of engineering, not to mention one of the worlds biggest miniature cloud tanks. BOSS was serious about this business, and invented and innovated its way forward.

All this wonderful technology was put on its ear after Jurrasic Park came on the scene. Millions of dollars invested in precision film-based equipment was now almost useless, and millions more were now being spent yearly upgrading software and workstations. This was the era of the Silicon Graphics workstation. It was not cheap, but it was powerful (relatively speaking). As has been learned across the industry in the past 20 years, this kind of pressure in the ever competitive VFX field has the ability to bring a company to its knees financially. Such was the eventual outcome of BOSS.

Alien 3 was still heavy in photochemical process, as was Batman Returns, but the digital tools were stretching their wings. New uses for rod puppetry in Alien 3 and digital flocking of animated bats in Batman continued to push the envelope of innovation – the new digital tools were not going to replace a smart and reasoned approach. The craft was redefining itself, and BOSS remained a VFX powerhouse. Focus on creativity, and innovation, with talented artists at the core. Artists make good work with any tool, not defined by it — BOSS was proof of that.

One of the best examples from this era of BOSS’s work was the Movie Cliffhanger. This film was a prime example of traditional and digital techniques married to dramatic effect. Mixed technique kept the audience guessing as to how it was done, and allowed the audience to stay in the action of the film, which would be unfilmable via live-action methods alone (at least with any degree of safety).

So many films, but so much achievement go overlooked in this tiny list. Let alone an awesome SIGGRAPH party in 1995.

BOSS in the digital era created visual effects for the film Multiplicity. Twinning an actor was not new to filmmaking, but the new digital tools allowed a level of refinement to the image that were difficult to achieve photochemically. Of particular note was the use of a video camera to record the actor’s performance from the position of the second character (using an 8mm video camera), and then play it back on a small video monitor while the second performance was being filmed, and standing in the position of character #1. This allows the actor to literally act with himself, and that comic timing was clear in the film.

It was demonstrated on an episode of Oprah. There were now three of her, but it was breakthrough at the time. One week turnaround on full digital visual effects with a motion control field recorder, and advanced compositing for television. Madness.

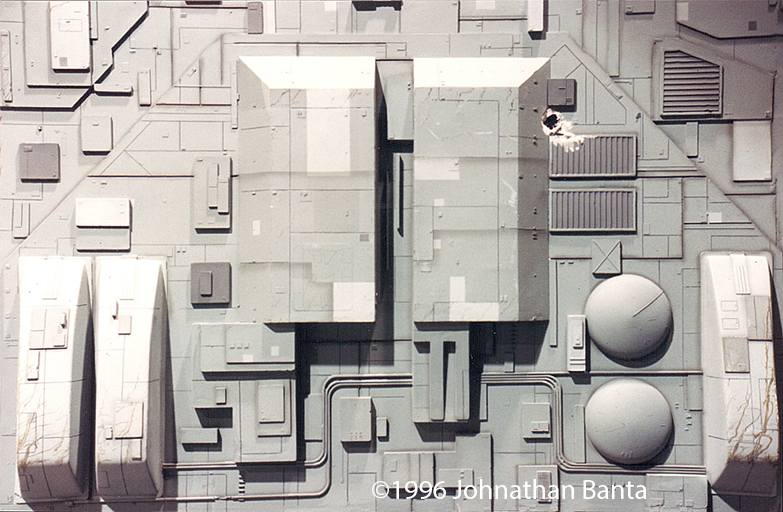

I joined BOSS film in 1996, to work on the “blockbuster” film Turbulence, as a texture and matte painter. I was on the digital team, in a candy store. I walked through the model shop every morning on my way to work (7:30am dailies, Aargh) and during the ever present “render walk” (documented by Bruce MacRae in the film A Sense Of Scale), what an amazing treat this was. All the film history, and the artists that made it happen. Working with Dave Jones (responsible for R2D2 on the CE3K Mothership, as well as on the tip of the airplane wing in the movie), and Greg Jein in the model shop I was able to unify approach to texture mapping from practical to digital, and even started originating decals for their models using desktop publishing methods. I was encouraging them to embrace the tool that was trying to replace them, and they were interested in it, as I was trying to make my job in texturing easier by originating the artwork, and learning from things that are real. That’s what BOSS was like. New tools, mash together, smart people, better product.

Fun.

Turbulence was vexed with a problem. Airplanes fly through storms, and there was no fluid simulation clouds available at the time. The final solution to the challenge was large fiberfill cloud canyons photographed under motion control, later filled with multiple scaling layers of digital cloud artwork (that I painted), by talented compositors. This is now fairly common practice in video games and compositing as multi-plane, but was unusual at the time, and solved the problem elegantly. As far as I recall it was Richard’s idea, but its origin could use more research, but it began an era where CGI was getting closer to the camera than the practical work.

One morning while waiting for a screening, we were discussing the state of visual effects in the digital era, and I lamented that the work of late was not measuring up to the work of Doug Trumbull, in Close Encounters, Star Trek, Blade Runner, and Silent Running. The response to my observation was from Dave Stewart, who listed all the same movies, followed by his name each time. Impressive. That is who I was working with near the end of BOSS. The best. Dave has sadly passed on.

As an aside, I did manage to fit a gag in the film. At one point a truck is stuck to the bottom of the airplane. It was the miniature, and needed a little touch up for final. I digitally altered the license plate to include the numbers 8055. This reads as “BOSS” if you look at it right. I swear this is the only time I have ever done this.

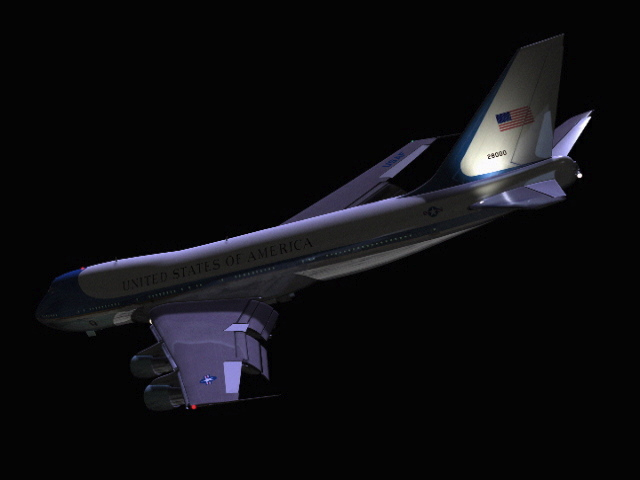

The work on Turbulence got us more work on Air Force One. Most likely because we had a big model of a 747. However we also built three other large planes and several fighter aircraft. It was quite a sight to see them around the shop. Yet again they would be flying among the clouds, but this time the plan was to thoroughly pre visualize the camera moves, and shoot motion control pan/tilt clouds from the bottom of a leer jet. Luckily California was suffering the effects of El Niño and the most spectacular cloud formations were off the coast. The method worked fairly well, despite the exposure change from the plexiglass canopy in front of the camera lens. It is likely that was never tried before, but there was no other solution present at the time.

Near the end on Air Force One, the digital team produced a ray traced render of the president’s airplane. It tumbled and reflected, and looked beautiful. Richard exclaimed “why am I paying for a hangar in Synchro?”.

Synchro is the airport hangar in Van Nuys, CA where several large airplane models suspended on motion controlled marionette rigs, danced with motion controlled cameras in computer controlled precision. Technical beauty, driven by the talented artists, but also the competition between digital and practical, pushing each one to outreach the other. So much great work in that film, despite it’s reputation for the final water crash (the result of constant production delays in decision making, re-staging of the shots from night to day, and the challenge of doing full water splash simulation with the software of 1996).

Richard, you had the stage because it needed to look real, and it was cool!

Desperate Measures was one of BOSS’s next films, and it was a great example of invisible effects, digital set extensions, pyro miniatures, and matte paintings. In the matte department I borrowed the digital QuickTake 100 camera belonging to one of the artists (Scott “Roscoe” David), and shot several elements I incorporated into the final matte painting of the prison – initially started by the legendary Michelle Moen. Not sure if this had any precedent, but it would be worth documenting that.

Soon after Starship Troopers landed at BOSS. There was a 18 foot version of the Roger Young space carrier suspended by a marionette rig – which really pushed the digital painting dept to remove wires over that much detail – once again at Synchro. There was also an 8 foot diameter potato shaped meteor built as well (an homage to the Empire Strikes Back hidden potato?). This level of detail is required in miniatures so that the specular highlights do not indicate the actual scale, and inform the audience that it is a miniature. However it proved to be still an insufficient scale to create a shot that joined the miniature to the full-size set in one long camera move. Starship Troopers is therefore one of the first examples of 3D CGI that actually gets closer to the camera than a miniature.

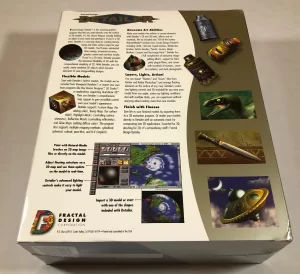

The opportunity to do this as CGI was a boon, and also a burden. The render farm was taxed heavily, and the SGI machines we normally worked on were tasked as render machines. I was asked to create a 3D paint pipeline that used the few Macintosh machines around the shop (as I had revived them from obscurity). There was some resistance as some hoped the render nightmare would end. I thought it was part of “the SGI priesthood” that existed in the early days of digital VFX, as many did not think the PC or Mac were capable of film level work. Either way, we eventually used the off the shelf 3D texturing program Fractal Design DETAILER,

in conjunction with photoshop to build the first set of textures, and refine them in the SGI pipeline. The burden of computational time and the advance of CGI to close up images resulted in a 18 foot miniature used as deep BG imagery. It seems counter-intuitive, but the results were fantastic.

in conjunction with photoshop to build the first set of textures, and refine them in the SGI pipeline. The burden of computational time and the advance of CGI to close up images resulted in a 18 foot miniature used as deep BG imagery. It seems counter-intuitive, but the results were fantastic.

As an aside, the Macintosh machines were used for a lot of Photoshop work. Matte painting and textures for all of the shows I was on used Photoshop and Adobe Illustrator. Illustrator was used to layout masks, and decals for the practical models as well. As for rendered 3D matte painting elements, and particle gags I used Electric Image and Adobe After Effects, rather than taking needed SGI assets from the floor. It was often the case that my SGI machine would be offline as a rendering node, and I was able to continue my work on the Macintosh.

About the time I left BOSS in mid 1997, The Parent Trap remake (under the direction of Jim Rygiel) was in progress, using the same technology and team that built the Multiplicity pipeline. The resulting work remains some of the best twinning work in a film to this day.

Sadly one month later BOSS was out of business. No more visiting pet dogs. No more guitar serenades. No more video game and pool room. No more barbecues in the lot. No more pet ravens we tried to teach to say ” RM * “. No more exploding airplane models in the back lot, or flame engulfed cliff faces. All I have is a half-apple box and memories of that era. It was alive when I left it, thus it remains so in my memory.

As I said before, Richard Edlund’s BOSS film studios was a powerhouse of creativity. I rather think it was named as it was, not because of the firearm, but because it was totally boss! It was never an example of exploit for profit, it was a clarion call to quality. It set the standard in many aspects of visual effects at the time, it also set the careers of many artists in the digital realm to geometric growth. Mostly, it taught us all a great lesson:

Innovate. Create. Most of all, have fun.

Thanks Richard.

AG

Notes:

Thank you to those concerned for any additional information.

* After writing this entry, I located an article of similar title (my original Boss Film – End Of An Era) in CINEFEX. This is not endorsed by the magazine. However, this blog endorses CINEFEX. The Title was Changed to its current name.

**Mark Stetson reveals: “In addition to your recollection, Boss’ original name was Boss Film Corporation, or BFC, which was an homage to the Mitchell BFC 65mm cameras that were the backbone of the studio’s original approach to large format VFX. BFC stood for Blimped Fox Camera…”

Very cool, thanks for sharing.

Great article. Love those pictures too. Richard and his BOSS FILM STUDIOS played an integral part in influencing my path in life and love for Cinema and Special Effects, and Visual Effects, including Make-up, Miniatures, Matte Painting, Mechanical Effects, Creature Effects, and Stop-motion Animation.