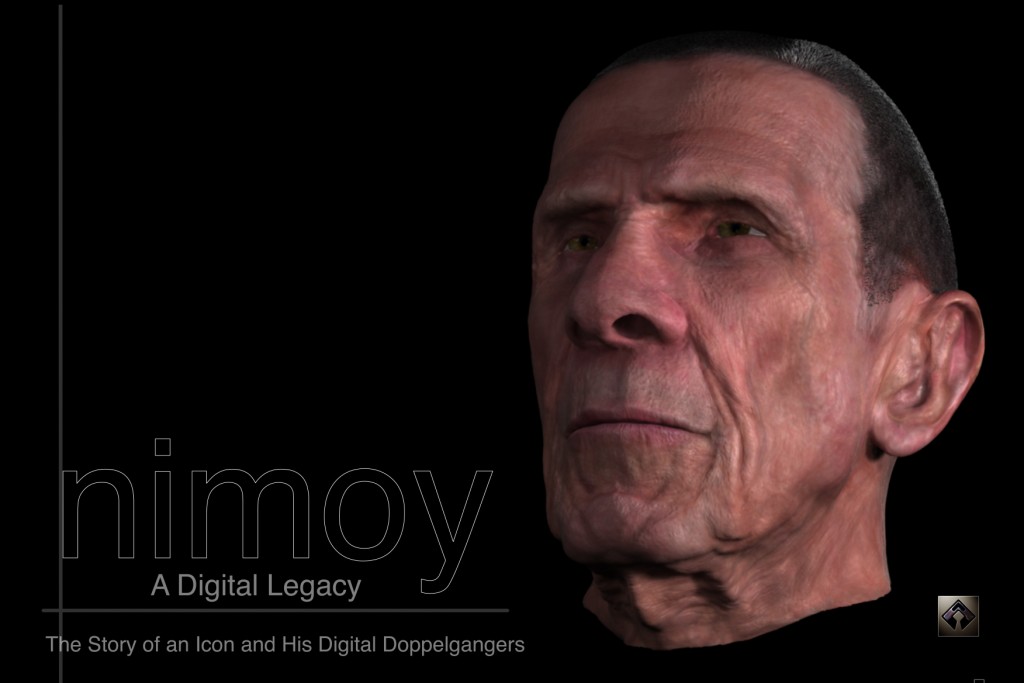

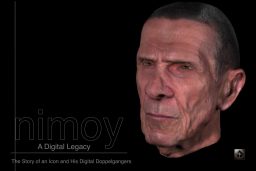

The Digital Legacy of One of the world’s first 3D scanned actors.

I’d hoped to have written this before it happened.

You never know how much you appreciate something, or someone until they are gone. I was one of the generation raised in a world where the name SPOCK meant something more than how to raise children. The character that Leonard Nimoy created on Star Trek gave was an ideal of logic, and personified our struggle to overcome or embrace emotion. Mr. Nimoy gave us an unforgettable performance, and was able to eventually springboard from this character and become an author, singer, screenwriter, and director. Unfortunately this intriguing individual was taken from the world due to a lifetime of smoking, which he publicly regretted.

Of all the accomplishments of Leonard Nimoy’s life, there is one in which he and the cast of Star Trek IV, which he directed, are also notable, which in many ways reflects the underlying science of their science fiction day job. They are the first actors ever to be scanned as a 3D model for computer visual effects in a major motion picture. This milestone is an important thread lurking in the background of Mr. Nimoy’s career.

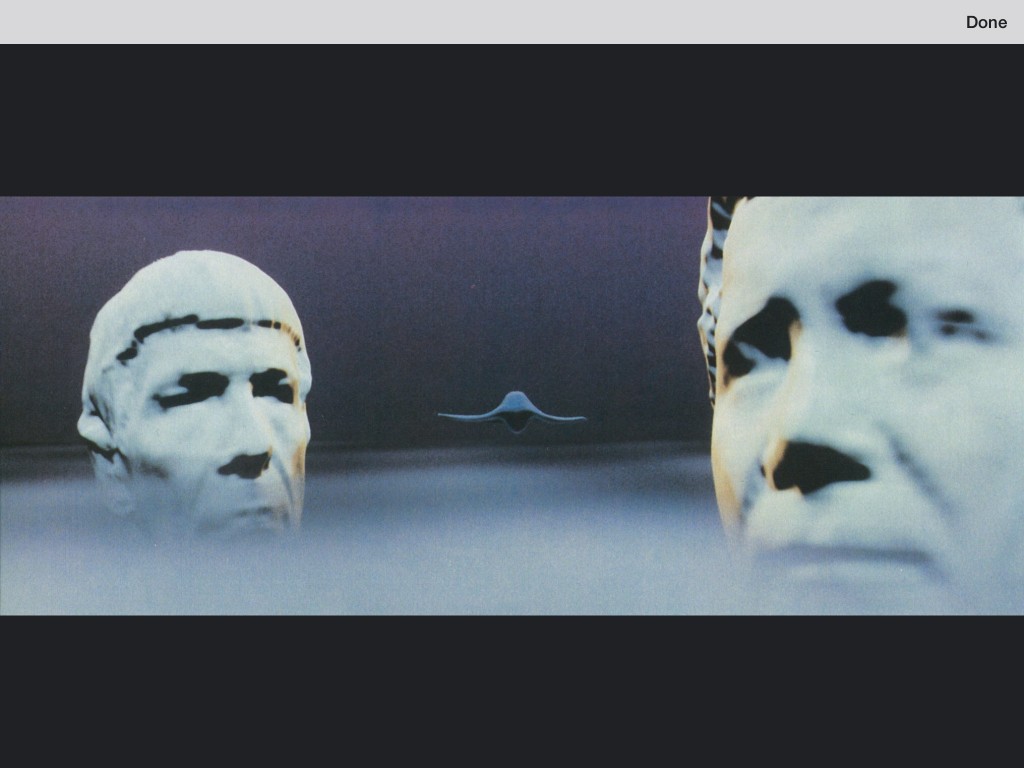

Star Trek IV embraces the oft-used mcGuffin of time travel to further the plot. In past Star Trek endeavors, time travel is depicted through flashing lights and unbalanced cameraman, or conveniently covered with dialogue spoken in past tense. Star Trek IV, under Nimoy’s direction, went a different route from the franchise’s normally stringent guideline of making the future look realistic, and instead used surreal imagery for the mental state of the characters as they transcend time.

To accomplish the task of propelling the crew through this metaphorical land, Ralph McQuarrie designed a dream-like journey in storyboard form, that used technology from the computer graphics division at ILM, who had previously floored audiences with their work on the Genesis planet in Star Trek II. In the sequence, busts of the actors would float amongst images suggesting water, and whale-shaped beings. Some images were photographed, but the standout shocker was the digital work which together contributed to a truly unique vision of time travel.

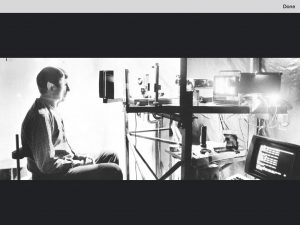

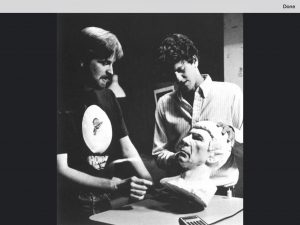

This sequence design required the likeness of each actor in the computer. The state of the art method at the time for computer graphics would have artists digitize a sculpture, or life-cast of an actor with a handheld digitizer pen, which had been done for several other projects up to then. However, a new company called CyberWare, in Monterey, CA, was called upon to use their brand new laser scanning system to directly scan the living actors, and produce digital models. A 256 x 512 (131K polygons) mesh emerged from the process, which Cinefex Magazine reports the co-supervisor as saying: “…[that] is all the resolution you’d want to have a face scanned out at.” The resulting models are crude by todays standard, but represent a milestone in computer generated imagery — considering this all took place prior to 1986. A styrofoam-milled version of the data was also produced for possible digitizing in case the data could not be used (there were some bad data points in the original scan that needed cleaning up at the time).

Cinefex (the major source of this information) reports that the rendering took weeks.

The Forgotten Journey

Once the film was finished, the digital models of the actors fell into a virtual abyss, since they no longer served any purpose. Well, no purpose the filmmakers envisioned, but the Spock scan re-emerged from time to time in SIGGRAPH presentations about geometric modeling . Not that the model is of any great quality, but the crude nature of the original data helps test new algorithms for cleaning and “up-resing” geometry. Many algorithms that 3D software use today for geometric manipulation have either been the result of, or used at some point to refine the Spock mesh.

It is interesting to note that though several actors were scanned at the time, it is only the images of Nimoy, and his digital mesh that are passed around — a testament to the impact of his character. Using the Spock model is always a favorite at the conference. The model is not easy to obtain as other standard early geometries like the Stanford Bunny, or Newell teapot are, but it is a highly prized mesh (and likely subject to some form of legal protection). It remains one of the holy grails in the black market of 3D models. To my knowledge, no other scan of Leonard Nimoy has ever been made (though I suspect ILM is holding out), and is easily under wraps if it had been.

Mr. Nimoy had semi-retired at one point, but he eventually started a working relationship with Bad Robot Productions, not only appearing in Star Trek (reboot), but also in JJ Abrams series FRINGE. — Where he almost always depicted himself without the use of digital tools. But then, that’s about the time I got to make a new 3D model of Leonard Nimoy.

This Ain’t Spock

First, a little history on how my involvement in a Digital Nimoy came to be:

I was a lead compositor and one of the general problem solvers for JJ Abrams FRINGE. It was also one of my duties to help create digital doubles of actors for several digital makeup transitions and effects. As with any high-end production in Hollywood, we started creating digital doubles with 3D scans of actors using the latest generation of 3D scanners. The quality of scans these days is vastly improved since 1985, but the process is still expensive. Nonetheless, when one actor is scheduled for digital work, it is within most television budgets to get them scanned. Unfortunately, when a story requires multiple actors to undergo digital manipulation, as was often the case in the series, the budget for 3D scanning grows thin.

We needed to try a simpler (read that as “cheaper”) approach for 3D scans of five different characters in a single episode. I set-out with Mike Kiyrlo, one of the Technical Directors on the show, to use a combination of off-the-shelf software, 3D tracking, and manual refinement to create the digital meshes. We had eight images of each actor photographed as they turned around in place, and nothing else. The first mesh required three days as we worked out the pipeline, but reasonable results could be achieved within a day of work for one artist once it was established (Thank you Christina Murguia).

The resulting models, though not as detailed as a modern 3D scan, had common underlying geometry and texture space, and were higher in density than the original Spock Mesh. The common geometric space, in a manner similar to the Star Trek IV time-dream sequence, allowed artists to morph actors and exchange texture maps where necessary. This facilitated practical makeup transfer from one actor to another, and various morphs between creature makeup stunt doubles and actors — maintaining the look developed by the makeup effects team on set. The method was the common way to create digital doubles on the series, (at least while I was there) with only occasional need for more refined scans. This was hand-built photogrammetry.

I had opportunity to work on another episode with Leonard Nimoy (we had previously shaved 15 years off his face for a flashback), in which he was atomized while saving others in ultimate sci-fi peril. After finishing that episode, Leonard Nimoy announced his retirement … again. Recognizing that he had come out of retirement once before, I proposed building a digiDouble of him, as his characters have the knack for coming back. It was not seriously considered.

At the end of the second season, I left the company to lead stereo conversion teams, and consult on stereo films around the world. The dream of the new digital Nimoy remained unrealized.

A Good Thing Keeps Coming Back

While I was away from the production of FRINGE, despite the fact that there was a digiDouble pipeline up and running at that VFX facility, the show runners chose students at Gnomon school to build a digital Nimoy for the episode entitled “Brown Betty.” That team created an animated likeness of Leonard on an inter-dimensional television screen. The result is a good effort, easily hand modeled, but its movement is not very convincing. The color correction hid most of the detail, and the texturing was not clearly discernible. It was an image sufficient for a drug-induced fantasy story, so reality was subjective anyway. It was a caricature, or cartoon of him in many ways.

Speaking of cartoons, Hollywood could not just let Leonard Nimoy retire. One more drug-induced storyline (a recurring theme in the series) — the famous animated episode of FRINGE — is an action packed adventure with William Bell voiced by (retired) Leonard Nimoy. The computer animated result loosely looked like him, but is a very stylized depiction. I can only guess as to how much effort was spent trying to recreate this likeness, and knowing that time is always a limiting factor in television production the results were good enough. In the end, I feel that his vocal performance is the strongest element that gives it credence as Leonard Nimoy, and not the digital model. Once again, not a perfect likeness but his presence was intimated.

There remained a need for a good 3D Leonard Nimoy.

Enough Backstory. What About My Nimoy mesh?

I returned later to work on part of the fourth season of FRINGE. One of the episodes I worked had Leonard Nimoy’s character William Bell trapped in the time-locking “amber” the show frequently used to freeze time and space anomalies (it’s a sci-fi show, no need to explain). Mr Nimoy was not available for the episode, but since his face would always be beneath the optical distortion caused by the amber, we could use a still photo composited on a body double. The world foolishly thought that atomizing William Bell in the second season finale, and Nimoy announcing his retirement was the end for that character — but this is a television show with Leonard Nimoy in it, and he was set to carry the last few episodes. My earlier intuition was proven as true.

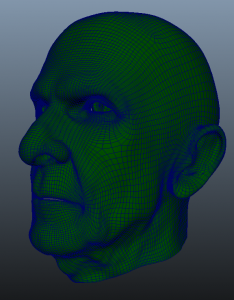

With the actor once again fully out of retirement, I saw this as an opportunity to build a useable asset for the future, and improve the quality of a Nimoy mesh. It was not planned for or budgeted. I was alone in my quest. Nevertheless, I took a few days after hours of my own time without pay as a learning exercise, and if I was lucky we could make use of it for the Amber episode, and future-proof the character for the series. I wanted to know how far I could push it in a short time.

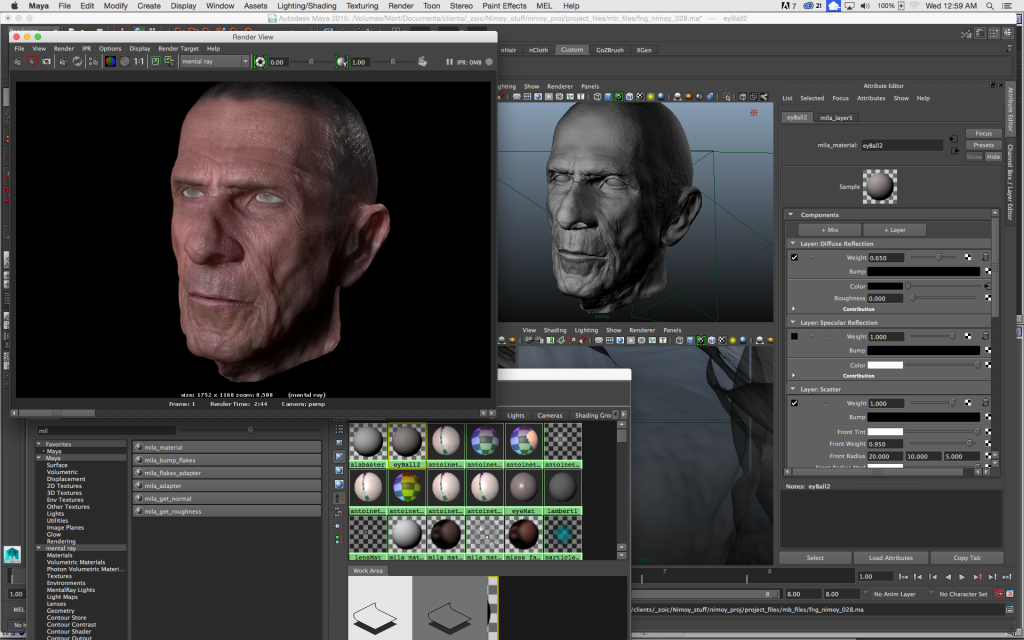

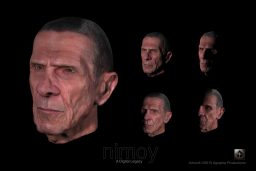

At this point in time there were no photogrammetry software solutions like Agisoft Photoscan in my pipeline, but the hand-modeled approach from 3D tracked cameras was available. The result would only ever be an approximation, not an accurate scan of the actor. I knew that my approach to building the model had some distinct advantages over common orthographic modeling. As I previously mentioned, the digiDouble pipeline is a form of simple photogrammetry based on accurate 3D-tracking. The key to the method is the 3D cameras, and not orthogonal views, or my ability to interpret perspective. Perspective modeling accounts for the distortion applied by the camera lens, and does a better job aligning features in 3D. Essentially, I was the Cyberware scanner, or photogrammetry engine. With all the points returned from my tracking, I pushed through the challenging task of refining the base model— one feature point at a time.

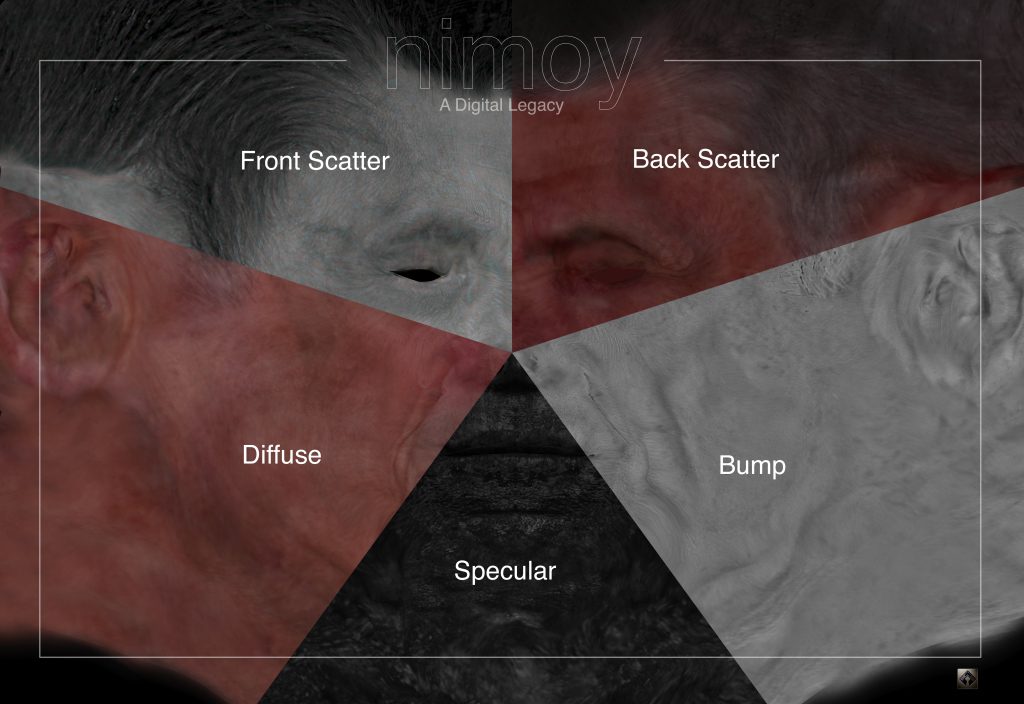

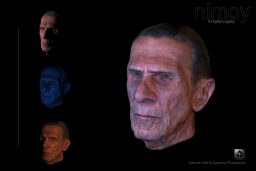

Texturing the final model would be the next challenge. A simple diffuse map of projected photography works for many digital doubles, but it has baked-in lighting, and no material properties that match human skin. Because my subject was shot from multiple angles, under varying lighting conditions, which is normally a negative set of circumstances for this kind of work, I had some specific advantages for texturing. I could treat the texture mapping in a manner similar to the work by Paul Debevec at the University of Southern California ICT. Although I did not have a light stage with 256 lights, I did have a series of images with a common ambient tone, and a directional light from a flash. I extracted specular, and occlusion maps for final rendering by averaging the projected image that overlapped. Further compositing work and channel manipulation allowed me to develop reasonable shallow-scattering, deep-scattering, and bump maps. In the end I was only using textures derived from the source material, and devolved into components that would look like skin (or so I hoped). Any original photography was only reference at this point.

Unfortunately I ran out of time, and despite one test, the model never made it to the screen. Although I had good results, the final shader tweaking was still in progress, as was the hair simulation, and the amount of post processing in compositing destroyed the illusion of texture the bump map provided, as I was using a lower polygon mesh. This kind of work requires a few more days to be sure (all right, 12 hours was insufficient), but the results were thrilling. I had a reasonable form, and good bump map, but lacked a lot of the middle-ground in detail that convinces the eye that it’s real. That was just a matter of time.

The hope to use a digital Nimoy was gone, but the internet chatter after the episode proved that the still photo worked fine. Everyone was convinced he was on-set for actual shooting of the scene. That’s VFX for you. Sorry internet, he was never there, and in truth this is the only episode where the amber had any practical elements.

I gained a lot of knowledge building a digital double of Leonard Nimoy, but not enough to make it in the short amount of time I had for the episode. I considered it a successful failure.

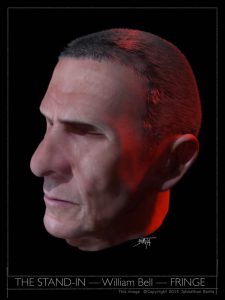

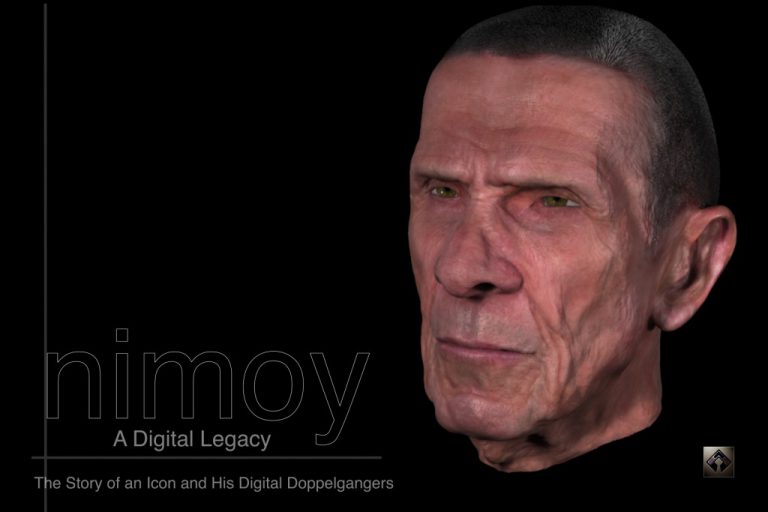

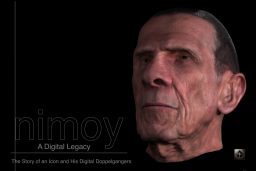

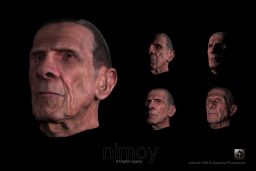

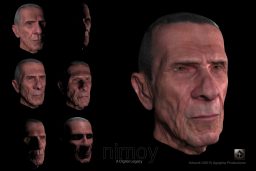

Passing of the Torch

Since the passing of Mr. Nimoy, and in preparation for this article, I dusted off the project, decided to update the shaders, and sculpt a little of the mid-level detail based on the maps I had derived in Pixologic zBrush. Many of the subtle nuances a real digital scan would procure are still missing, but using a bump map, some high-pass filtering as masks, and a fair amount of hand-sculpting, I have reached a more reasonable result. Despite the assertion of polygon count in 1985, my model sits at about 1.5 million polygons. At this point I still feel it is not 100% ready for on-camera work, but I am pleased enough with the result, since I am never putting it in a show. Once again I have used it as a research platform for skin shaders, and sculpting — honoring the legacy of any digital Nimoy mesh, that of testing things out. It is an artistic interpretation of the data, but one that I hope honors Leonard Nimoy.

I share this digital Nimoy rendering here for your enjoyment, and as a tribute to the man I ran home to at 4pm every day after school to watch in televised reruns of Star Trek, and In Search Of. Little did I know how much he affected my life, until I look back over it. This art is for him.

Thank you Leonard, my Twitter-adopted Grandpa. Your legacy in the digital realm does not go unnoticed.

AG

Post article:

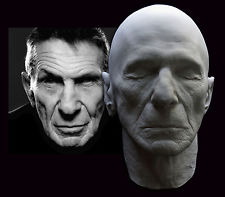

Years after finishing this article, photo of this plaster casting of Leonard Nimoy from the same time period came across my internet search. His cheeks, long with age were easily compressed by the moulding material at the time, which speaks well of the digital scanning process. It is here as a comparison to my digital work.

*There is a movement to create a digital Leonard Nimoy on the internet. No solicitation of this geometry will be entertained. No texture maps shared. Only the Nimoy Estate will have that privilege if they so choose, as this is now an original work of art, based on reference. The original data is not in my possession.

Pingback: Fringe to Falling Skies — The Unwanted Rise of Digital Makeup - AGRAPHA Productions

Dear Friend,

Did not you want to print in 3d this headsculpt in the 1:6 scale? It would give the best action figure of the Leonard Nimoy like William Bell! Congrats! Wonderful work! It was the best representation of the old Nimoy! Hugs from Brazil.

Best Regards,

Rodrigo