It Came From the 1990’s

Okay, this will take a little bit of back-story…

In 1997, I started to write an article in conjunction with Digital Domain’s Andre Bustanoby (fresh off of Titanic VFX) for the (now archival) website VFXHQ. This article was to chronicle what we saw as the beginning of a new methodology in VFX — a blending of practical makeup and digital tools. We envisioned that makeup artists would embrace this new realm and create wondrous new characters with new tools and old know-how. After all, the successful Jurassic Park was a hybrid film, combining the best of practical FX with digital FX, as were many effects on Death Becomes Her , Species, and Star Trek: First Contact – even lesser budgeted Deep Rising. Not to mention the work being done at DD at the time, for the Bjork Hunter video, and the multitude of random morph from actor to actor in makeup. (There were so many early adopters, that it is hard to codify them all without a heavily researched timeline. Kudos to you all!)

We had identified a trend, or so we thought.

Instead, JarJar Binks started a different trend and took the filmmaking world by storm, with its photo-real digital actors (not just a creature), followed closely by Gollum in the Lord of the Rings series and soon after by Davy Jones in the Pirates of the Caribbean series. The makeup folk recoiled in horror as their livelihood seemed usurped with digital computers, inverse kinematics and sub-surface scattering whatnots, nearly overnight. Similar to how stop motion animation shriveled and died after Jurassic Park, the whole world had turned upside down, and makeup effects were lauded as cheesy and irrelevant. The audience would demand only perfect, digital actors from here on out…

Or, so they thought.

There were always those voices that upheld the ways of practical makeup, and that puppet monsters were preferable to all the digital chicanery. They became adamant detractors of the new technology, and entrenched themselves within their opinion. Opposing voices championed replacing special effects tricks with scene simulation, constantly citing limitations of physical reality, and the minute detail that could be added up to the very last moment of production. This tumult of opinions continues to this day, with one camp decrying the contribution of the other. A subconscious animosity exists between them, who both want to shine in their chosen field of expertise, and who see themselves constantly competing for the same brass ring.

It looked as if that early trend may just have been a necessity until the technology evolved. Muscle and skin simulations, ever improving eye models, all extremely fascinating stuff — as long as it could be done cheaper-than-last-time. Nonetheless with a diminished role, makeup effects carved out a niche in the new market, constantly in fear of being replaced in post (Which happens a lot).

It’s Getting Old in Here

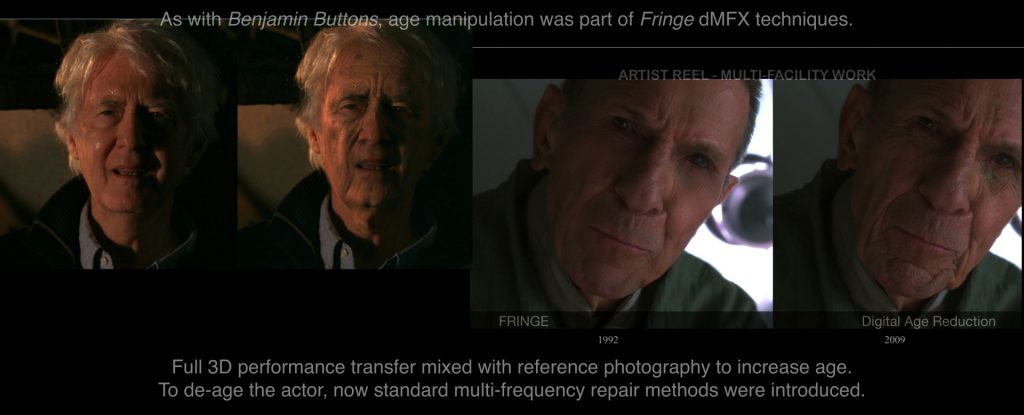

In 2006 and 2008, two notable films came out that advanced digital makeup to the forefront, and actually started using it as a term publicly. X-men: The Last Stand, and The Curious Case of Benjamin Buttons manipulated the age of actors who are currently older or younger than the writers determined they should be. Changing the age of actors has been the bailiwick of makeup effects forever (Dick Smith famously changing Dustin Hoffman to 121 year old man in Little Big man, or numerous other examples), but these were the first high-profile examples of doing so with digital tools — that were effective. Admittedly, they relied upon the eye of Greg Cannom and Rick Baker, and sought out and respected their makeup artists opinion.

To see Brad Pitt walk into the light, in his middle age, looking as though he were 26 years old again was truly stunning. The inverse of aging him with full three-dimensional computer graphics further impressed, but did not deliver the same smack-you-in-the-face reaction. If you can remove that annoying age from an actor, so they can play a role in their prime, that was what interested most people in Hollywood. With this you had their attention. Unfortunately that is what the understanding of digital makeup quickly became. Not the old guy, but the young whippersnapper tearing up the screen. Digital makeup was just for changing age, removing blemishes, tucking a tummy (as I had to do to a famous singer in a concert film who shall remain nameless because he can afford lawyers, but not a personal trainer), or making Scarlett Johansson’s clone look even more flawless (thanks, and shame on you Michael Bay).

But let’s be quiet about it all. There is actually so much of this going on, and the clandestine nature of it so pervasive, it is impossible to chronicle all the participants (rife for another list). This kind of digital makeup is known around the town, but the artists are the best kept secret in Hollywood.

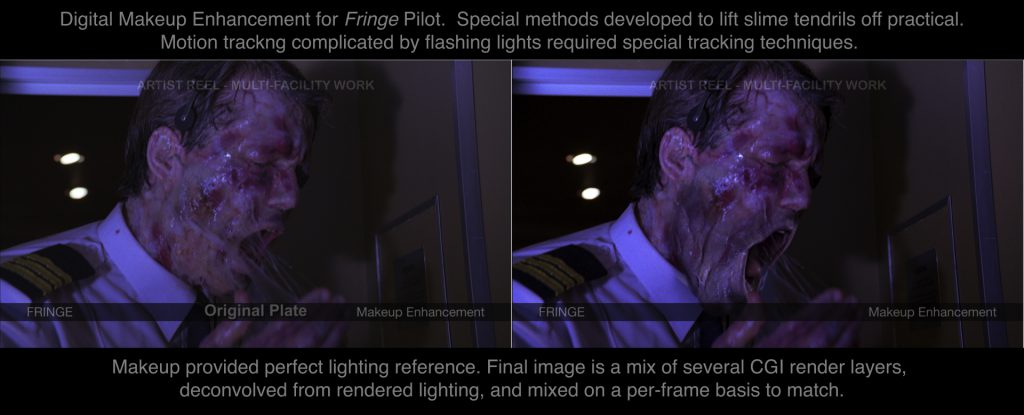

2008 also proved to be a pivotal year for the original use of digital makeup. Acclaimed director J.J. Abrams had a new television series called FRINGE. I had the honor to work with an innovative crew on the series, and in a way finally got to write a chapter about digital makeup — not only as an ‘Observer‘, but a participant.

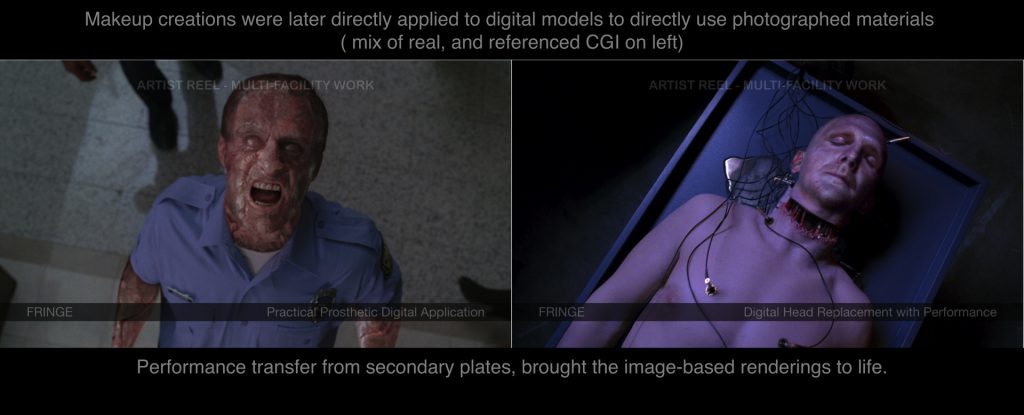

On the FRINGE

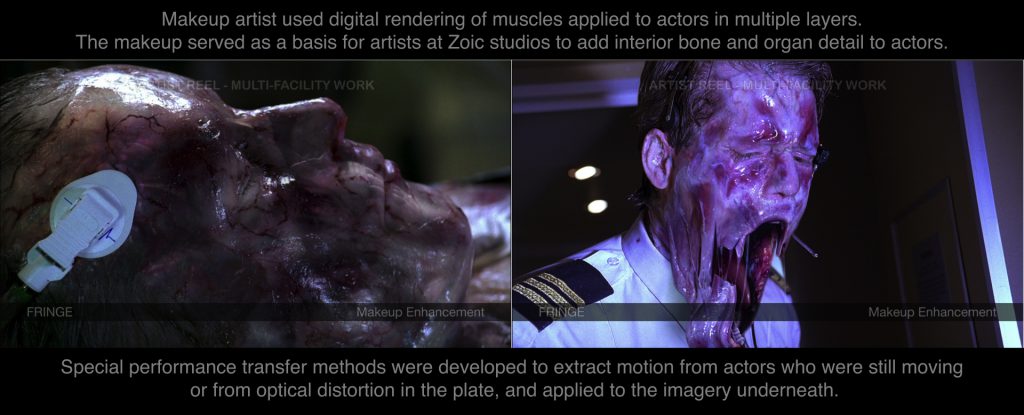

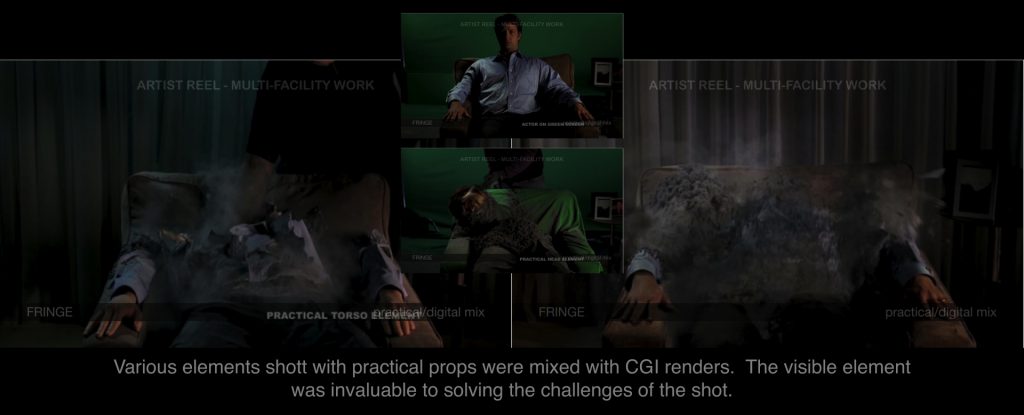

As filmmakers, but also fans of practical imagery mixed with digital technology, the creative staff of the television series FRINGE continually asked for methodology literally outside the box. The production engendered good working relationships with makeup effects companies to start the process, with full intent to finish it off later. It was common to use actors in makeup, or practical elements and add digital trickery, because it kept the audience guessing, and gave actors something to react to. I was one of the lead artists on the team that did the work (interview here), and we melted faces, altered the age of people both directions, and did horrible things to them on a weekly basis — almost always based on makeup worn by actors. Just enough of a trick to throw the audience off from spotting how it was done, and just enough altering of reality to make it memorable. It was a winning combination.

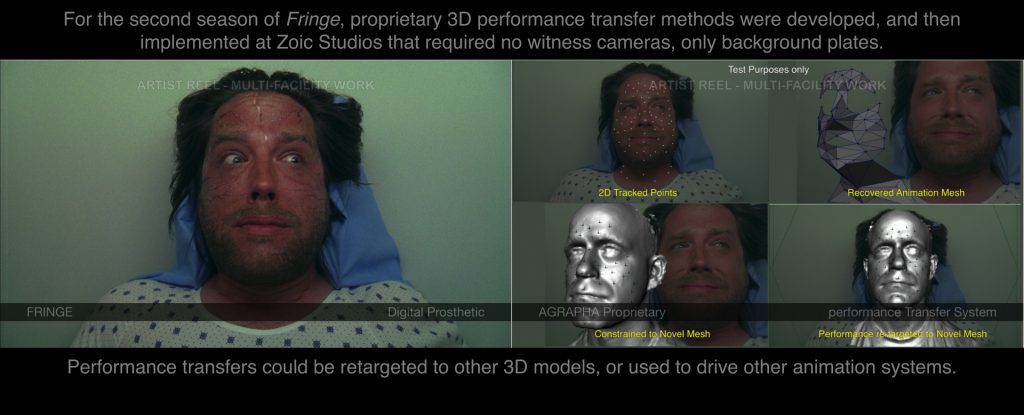

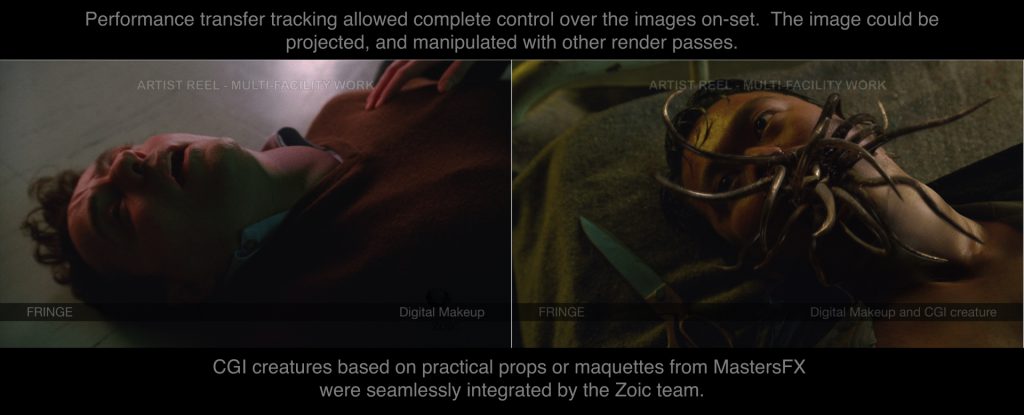

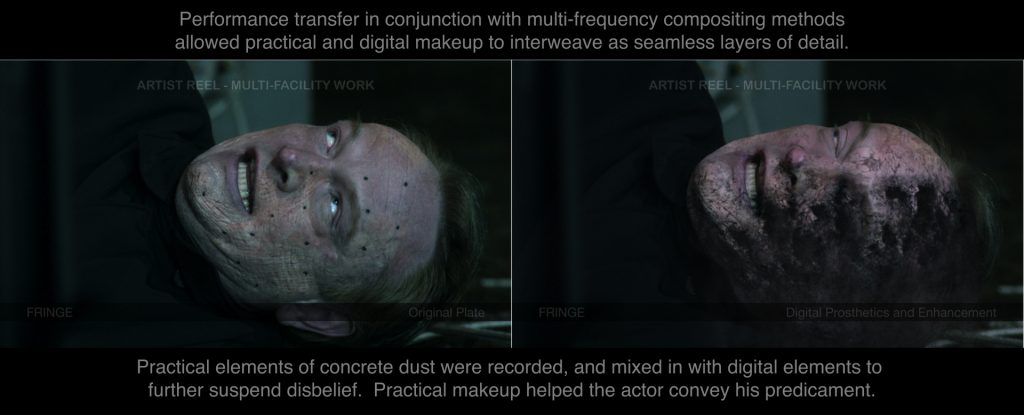

The writers threw ever-increasing challenges at us, and I found the more often we based our solutions on actual created items, or photographed elements (even if we shot them ourselves), the more approval we got from the creative team. So to accommodate the need, I developed new methods for performance transfer based on my work on large IMAX stereo3D converted films, and in conjunction with the few artists working on the project, we were able to push the actors performance onto digital characters, and move seamlessly between them and their makeup enhanced versions. One episode allowed us to take the horrible scarring from several other actors, and apply an amalgam of them digitally to an entirely different actor who could not wear the makeup on-set for various reasons. Digital Makeup was not just for cleaning up blemishes, but also for bringing characters to life with multiple sampled bits of reality, and the new sleight-of-hand.

The fans loved it. I remember being at the Visual Effects Society Awards, as the work of our team showed on the big screen. The whole room had just eaten, and FRINGE was announced as the winner for the category of best VFX in a series. A collective groan (maybe a gag or two) erupted from hardened visual effects artists as an airplane pilot on the big screen showing the submission video dissolved into a puddle of slime and goo. All those long hours putting that shot together —the tracking, lifting the slime off the makeup and reapply it over the modified imagery, driving secondary systems from pixel motion, mixing in the 3D rendered elements, and warping a found photo of a cow tongue — all paid off. I loved it at that moment too.

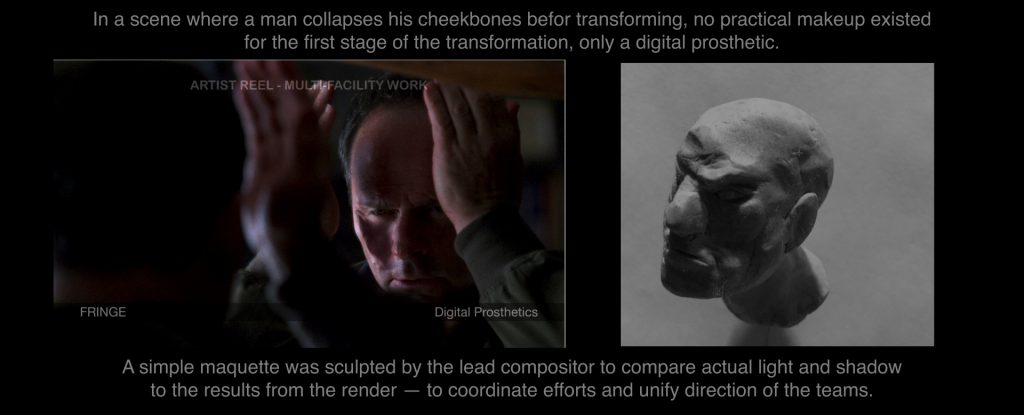

In the pantheon of television production, what we did was merely labeled Visual Effects, and despite any effort to coordinate, we were unable to directly plan with the makeup effects department. Too many layers of production, and moving too fast. Luckily the VFX decisions being made at the outset of production made sense most of the time. I kept clay at my desk so I could quickly sculpt out ideas, rather than gesticulate wildly in the air while saying words that did not communicate much of what I was thinking. I was not the creative director of the show, but a hastily sculpted maquette, or analysis of the effects as a physical force put the whole team on the same page as a jumping-off point — and to a degree influenced the world of the series. The physical visual sculpt was something we could light, and look at, as opposed to imagine. Though not originated by the makeup folk, it leaned toward their process.

In the end, we could only mimic what was done, ask for reference, occasionally get a scan of a puppet and do our best to work it out. Rarely we got the physical prop, or 3D scans of them. The result was something relegated to the post team to work with after-the-fact, with little knowledge of what went on before. Luckily everyone who revolved through that team brought their “A-Game.” But hey, this is how television VFX have always worked. Departments are clearly marked on the trailer. Only the producer makes them talk.

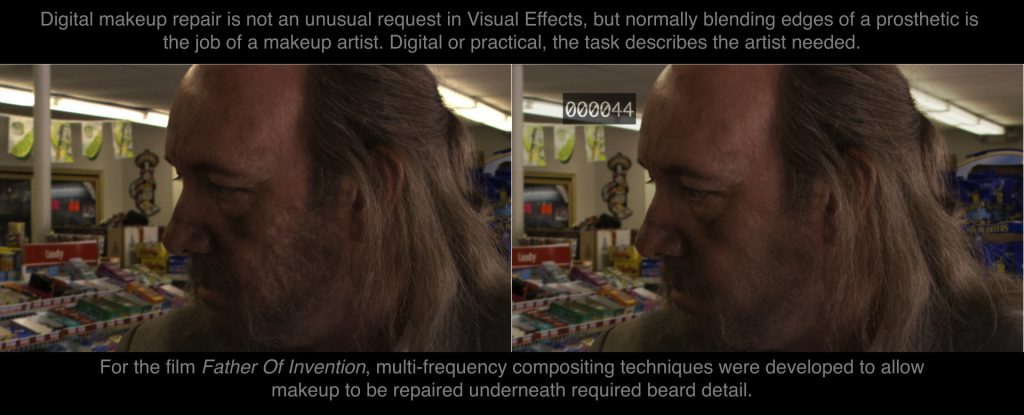

I was constantly repurposing prior work and research into the series, building up a common toolset, and relying the artistry of those on my team. Methods developed on the movie Father of Invention to fix makeup seams, were re-purposed to manipulate the age of Leonard Nimoy and John Noble. (As an aside, here is an article on the dMFX work, and recreation of “Digital Nimoy” and makeup transfer systems for Fringe and beyond). I would work off-and-on on the show over the next few years — always reassigned back to the production when they needed heavy makeup or matte paintings.

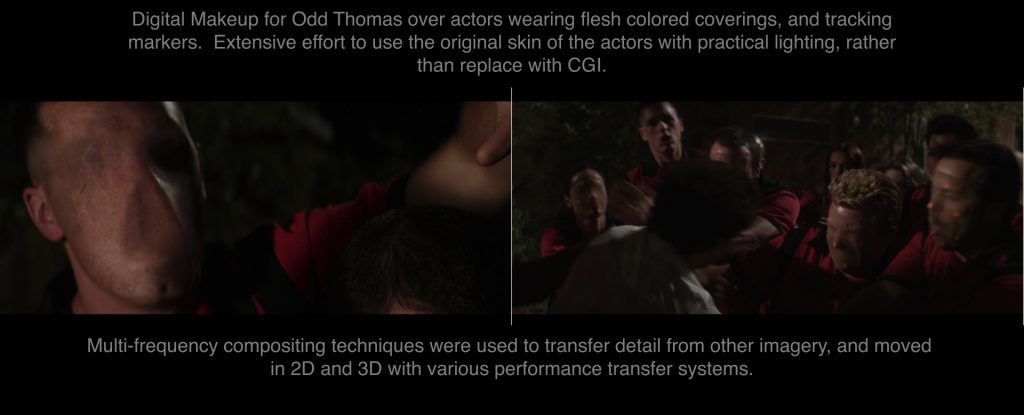

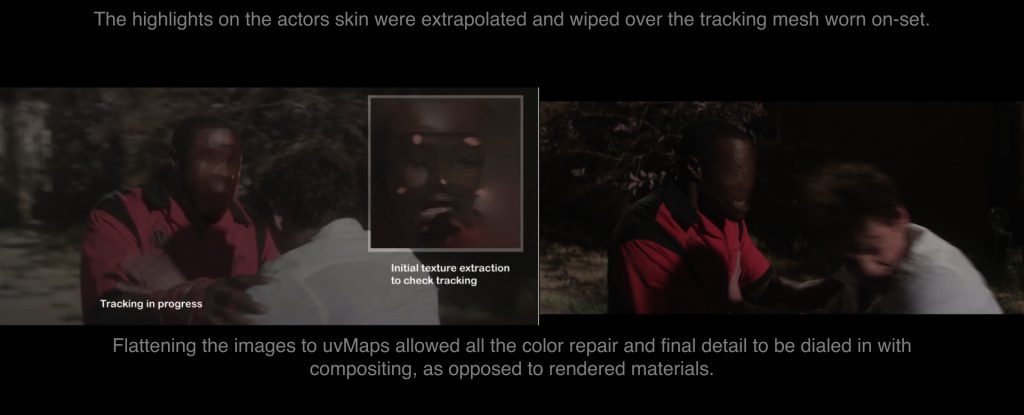

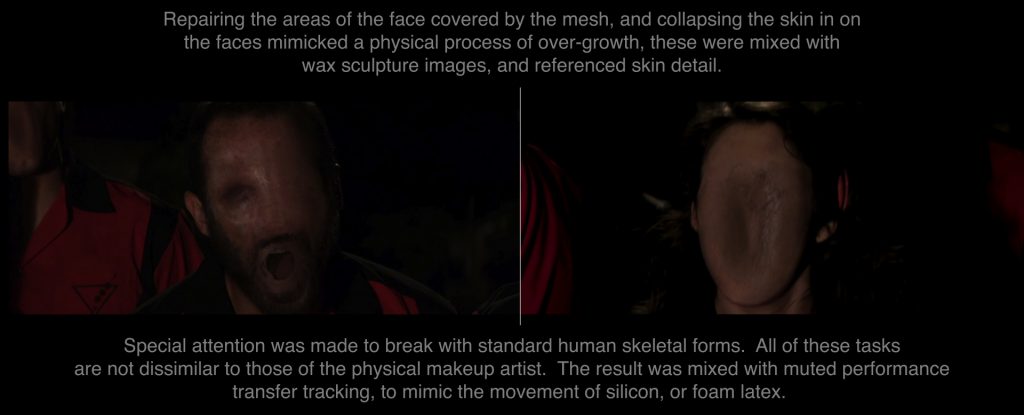

A few years after working on the series, there was more work for Stephen Sommers’ (director of the aforementioned Deep Rising) new film, Odd Thomas — in which I could improve a lot of the methodology I cooked up in the previous years (referred by my employer at the last studio, how nice). This time I had to create faceless demons from actors with giant pink tracking markers and panty hose on their faces. It was an incredibly fun exercise in design, and a thrilling result — one in which I retained, warped, or stretched pieces of the actors own flesh into new configurations with animated paintings and 3D models tracked to match. I could have just replaced the faces altogether with digital characters, but sampling reality as much as possible improved the final quality of the image, because I used the lighting photographed from the plate, and only augmented where it was necessary. I grafted, glued, painted, and enhanced the actors face with a variety of tools to make a new character driven by their on-screen performance.

Certainly sounds like makeup to me.

The Original Digital Tools Were Hands

I started out doing practical creature effects before computers came along, so had some idea of what the processes are — despite the fact that techniques have changed so much since I actually attached monkey masks to the faces of my cousins, and friends at school. Skin-to-skin tracking was essentially digital glue, and compositing the art of blending edges. Digital sculpting was, well, sculpting, and digital characters are puppets (Andy Serkis is a digital puppeteer or suit performer).

The analogies continued. I then realized that digital makeup required a level of expertise not commonly taught in schools, which I and the people I had worked with had learned on our own (hence my earlier reference to jumping assignments). Similarly, many skills required to make something look real are had amongst special makeup effects artists (the uncanny valley is generally not a term applied to physical makeup effects). All traditional makeup artists lacked were the digital equivalents of their toolset to make the transition, and the digital artists lacked the advantages of physical reality.

There are always the few individuals in every VFX company (unless it is a company like LOLA, where everyone does digital makeup, and keeps doing so brilliantly) who have the proper skill set, or way of seeing a challenge that makes them the ones assigned to a job. It is similar as casting an actor for a part. They know how to do this, and keep getting asked to do it. They might not be any good at anything else (odd as they obviously are), but they can do that thing everyone else can’t seem to grasp. They become a specialist. In makeup shops it seems to be the artist who can sculpt on the computer, has a 3D printer, or can illustrate contact lenses in Photoshop that finds a way to use it in their daily work (unless the company is LEGACY who broke the barrier to technology long ago, and keeps doing so brilliantly).

But why just hope for the individual who “gets it?” This hybrid, specialized skill set needs to be codified, trained, refined, and passed along. We only know what we know by the Dick Smiths, and James Blinns that came before us, and passed their knowledge along. It’s only through passing on knowledge that any fruit of it can form. Thus, I determined, with my meager contributions to the art form (I’m no Dick Smith, and this isn’t Benjamin Buttons yet), to apply the term digital makeup as an actual category, and dMFX artists as makeup artists for the new age, knowledgeable of both worlds of character creation. No more war between practical and digital, but a blending of the two. Rather than battle to the death, reach across, evolve the art and become more capable for it.

Makeup is an art, not just a halloween mask. Foam rubber and digital bits are tools. There is no reason to keep them apart, despite the many entrenched forces that cannot accept the unfamiliar. Digital makeup is an art, not a software program.

The Brave New World

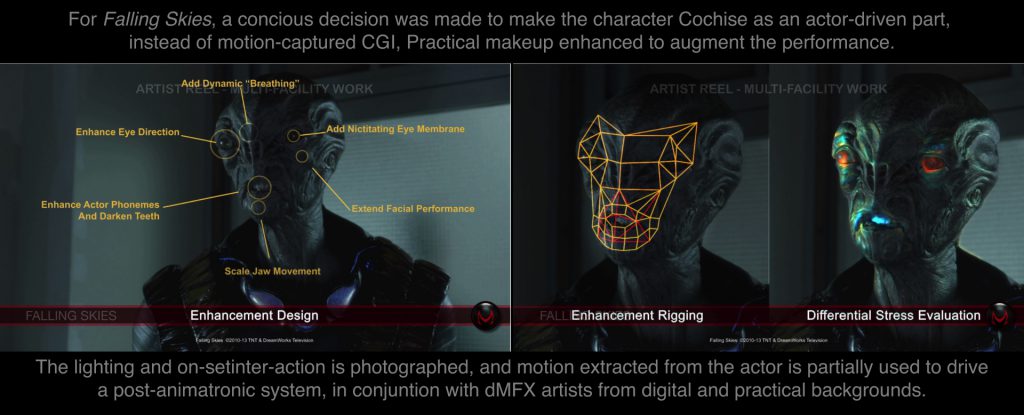

Since its second season, the practical makeup on FRINGE was the work of MastersFX. Todd Masters has been involved in crossover digital technology for a long time, famously for the appearance of the Borg Queen in Star Trek: First Contact. (Great interview on the Blu-Ray about it). The aforementioned Andre Bustanoby (who was fresh off his work at Stan Winston Digital) was also at that company, and we tried to coordinate on the FRINGE effects, but to little avail. Between us the push to bring dMFX (as we are now calling it) into the mainstream began in 2012 for the Steven Spielberg television series Falling Skies.

His name is Cochise, and is a hybrid of Doug Jones acting from behind one-inch of foam latex deftly applied by the makeup team, and digital-post animatronics applied by some of those same artists to the makeup after the fact. At first there was a concern that the makeup would hinder the actor, and that only a CGI replacement would work. Luckily this was not the first character for Doug Jones made up of a lot of rubber glued to his face. He is well versed in the art of suit acting and creates endearing characters, but it was up to the dMFX team to work in concert with him, and enhance the emotion he brought to the role.

For this type of enhanced character, it is the job of the dMFX artists to read the performance of the actor. Understand his gestures, and learn to complete phonemes, blinks, and emotions that he can only intimate. Doug is a fantastic actor, and breathes so much life into the character. The dMFX team reads that performance in post, and delivers that emotion to the original image (rendered in real time on-set with the other actors, lit and lensed by professional cinematographers, and directed by award winning directors). It is truly a team effort, and part of the plan from the outset.

Doug also plays his own father in the series — which seems difficult for any actor to play against due to filming requirements, and time in the makeup chair — in concert with the dMFX team, a wholly new individual with different ticks, reactions, and facial shapes emerges. When first starting that character we wondered how we would differentiate him as an individual, but his seasoned, floppy-lipped, abrupt response surprised us all, especially with the sheepish “black prince” Cochise at his side.

Unlike a CGI creation, Doug is a member of the ensemble cast, as many behind-the-scenes photos show them joking around between setups. That relationship helps the actor, and the hybrid performance removes the foam latex from the mind of the audience. The artists who sculpted, ran the foam, applied the glue and paint, help his performance show through later with digital artists in their midst.

I’ll never forget the email that said “Steven Spielberg likes our Cochise.” High praise for sure, and a great motivator to make it the best it can be. When fans of the show in live-tweet mode react to an emotional performance from Cochise, we can tell which parts Doug originated, and which parts we gave the hard-sell. It is a privilege to work with artists of this calibre, and feel the emotional effect on the audience.

Whats In A Name?

You may have noted the term “digital animatronics.” In dMFX we must name processes as they are. In makeup effects, it is application, animatronics, and puppetry. They use cable pulls, bladder gags, and various physical items to move the rubber and make it look alive. Thus digital cable pulls, digital application, digital bladder gags, etc. By assuming the nomenclature of the makeup effects artist we better define the process. No magic words. No slogans. Just describe what it is. The corollary is also true, as Andy Serkis runs around in a gray leotard, and Doug Jones motion capture suit just happens to look like an alien. By throwing it into a technical term, it seems as something almost anyone can do and get technical results. Not motion capture, but acting. This is a performance driven, post-animatronic enhanced character. It is never CGI.

dMFX artists are not just digital artists living amongst the backrooms of the makeup house and calling themselves something different, they are also makeup effects artists doing 3D tracking, compositing, and photogrammetry as well. Practical effects artists now understand how multiple render passes mix together to form an illusion of reality, and what effect subsurface scattering has on a final image. It is not beyond them to actually sculpt what they need, and then turn it into a 3D model for later inclusion. As an example, in Falling Skies, a sculpted prosthetic was scanned into 3D, rendered, and digitally applied to an actor already wearing other prosthetics for a battle sequence, rather than sculpt it digitally. The skill sets are crossing over, and discussions on which part is to be digital or practical are common, as opposed to arguments over who is stealing whose job. They are only in the back rooms because that is where they can turn off the lights for their monitors.

This is more than painting out a wrinkle or two. It is dMFX.

It is simple to say that this is nothing new. This kind of crossover has been going on since the advent of digital, but one cannot deny the tension. Even the brilliant work of the teams on Lord Of The Rings were this type of digital/practical crossover (the Mouth of Sauran as a prime example), and now during The Hobbit it seems easier to replace the on-set work (though anyone other than WETA might challenge that notion). Crossover work has been deemed a necessity in the past. Maybe it is an evolution of the art instead.

The techniques continue to evolve, which is one evidence of the latter, especially in the case of the visuals for Hemlock Grove. The team at MastersFX created a new variant on the werewolf transformation for the second season of the Netflix series, for which whole new dMFX techniques were developed. Photographing a change-O head as Rick Baker did in American Werewolf is now a standard technique, but digital compositing had not evolved when that film was made. With those techniques now standard, we can 3D track both actor and puppet performances and blend them together. We lift the skin off the actor, and graft it to the puppet, and grab motion and twisting flesh from the puppet and reapply it to the actor. Both images provide a sense of reality that fools the eye as they are glued together in compositing, and brought further to life with post-animatronics.

For a scene where we had to re-grow a characters arm, which easily could have involved a complex particle and flesh simulation, as well as morphing surface shapes, it was simple effective ingenuity that worked best. Rubber, slime, and performance of a person with matching hair under a green screen hood, mixed with a 3D recreation of the actual wolf puppet, all composited over an actor, who drove the performance.

It used to be the case that the creature shop and VFX were housed together. Now it is rare to see a shop and VFX team. In the age of digital, crossover methods have greater effect if they are planned and executed properly. The job is to create an illusion, much more than a Matrix-style alternate reality in which you get to point a camera. Maybe one solution no longer fits all. Instead of creating a makeup or puppet character, and throwing it over the fence to the lowest bidder to finish up or replace — why not let the makeup effects artist finish the character they promised to build? With digital tools, and practical capability they have everything they need to make up new realities that fool the audience at a better price point.

Here is a sample of multiple dMFX methods:

Here is the full Before and After submission for the Visual Effects Society nominated work:

Reaction

It is hard to imagine that anyone would object to such a natural mixing of the technique, but people have their reasons. Yet the opposite is true that there are many who recognize the advantage dMFX provides, and assure others that it is “the right way to do it.” One must assume for the first group that change is hard to accept, or there is also the possibility that hybrid may just be a temporary crossover from a dead art form. Are those who champion practical effects just nostalgic, or is the uncanny valley too much work to fight all the time? The idea of mixing the techniques is not as natural as we like to assume.

There are roadblocks.

At a digital makeup conference held by the Motion Picture Makeup Academy — set up to sing the praises of all the work by Greg Cannom, Digital Domain, Rick Baker, and LOLA VFX — the edict that “no makeup artist will be a digital artist, and no digital artist will EVER be a makeup artist,” was spoken. Upon questioning Rick Baker disagreed. Kind of an odd sentence to utter to the crowd, since that is why they came to the event.

Initially the VES awards rejected the admittance of Cochise as an animated character. It was seemingly so effective (we liked thinking that anyway) that they just thought it a man in a rubber suit, but recanted when we explained the level of sophistication that went into the character. Of all the things that engender visual effects, this would seem a natural candidate. Odd that no one would recognize it being done. It was nice to see that minds can change, but Cochise did not get nominated, despite his inclusion being a great leap forward.

There is also hope.

The zeitgeist these days pushes for more practical elements as part of the VFX solution. Audiences grow tired of the ten-thousand destruction simulations, and CGI actors and characters who we are supposed to believe in. They look back at the rubber puppets and model spacecraft of the 1980s, and remember the thrill. Perhaps the balance is about to be struck.

Makeup artists use computers. Talented people with proper digital tools can create makeup. its time they are mixed, and recognized for their skill. For the upcoming generation of artists, this is not anomalous to consider. Fans of genre films and television love what dMFX promises to become, and fully embrace it as one of the leading methods of the future. With many budding dMFX artists growing up in both camps today, it is incumbent that as much as possible, there is a place for them to go.

It is fitting that J.J. Abrams is getting the VES Visionary Award for 2015 in the same year that Hemlock Grove is nominated for a VES award for the werewolf transformation ( which also included a digital puppet by Zoic Studios). Although not the only director to take a hybrid technique for visual effects, his decision to mix practical makeup and digital has pushed much underlying methodology for it, which made the werewolf possible. dMFX techniques have just closed their first loop. Where can they go from here?

To all those in the community utilizing dMFX, you are singular artists doing something new that few people know. If the observation stuck in our heads from 1997 can help storytellers tell their story, then lets teach them to everyone.

AG

*So many artists contributed to all this work, so many more will. Here are a few:

Rodrigo Dorsch, Michael Kirylo, SallyAnne Massimini, Christina (Boice) Muguria, Eric McAvoy, Jason Jue, Jesse Sigalow, Dave Funston, Dave Zeevalk, Andrew Orloff, Todd Masters, Barry Berman, Scott Kilburn, Lauren Coogan, Chris Brown, Chris Wright, Sam Polin, Dan Rebert, All the MastersFX crew, Zoic Studios, Joe Grossberg, and so many others my feeble memory misses…. thanks all!

We are all in debt to Dick Smith, who broke the silence. God Speed, sir.

Pingback: Fringe to Falling Skies — The Unwanted Rise of Digital Makeup | Sci-Fi Talk

Pingback: Tracking for Fringe Effect — Performance Transfer in Production – AGRAPHA Productions

Pingback: Digital Makeup Chronicles 2 — The Life of Brian – AGRAPHA Productions