I’d Like To Sleep For A Week.

I wrote this article in 2014:

As I sit here working another wee hour on a project, I am beginning to envy my cat. As is mostly the case, I am awake because I love what I do, and fitting in another job, or research project, book (or blog) is the reason the glowing screen and pixels beckon me from my bed. There is just not time enough to do all that I must, work for the people I associate with, and get sleep. Most of the time this is my choice, as I learn more about the craft at a faster pace than if I were to just focus my time 9 to 5. Is it a wise choice to work like this? I’ll let you know when I have a clear answer, but for the most part this late work is the result of my choices. At least that is what I tell myself. I must gain knowledge, and work to eat. Housecats do not.

As VFX artists, we are seemingly all excited about our careers much more than standard work-a-day employment because what we do, though at times stressful, is very cool. We make alien worlds, ancient civilizations, and unwelcome three headed house guests a reality on screen. For many of us it is a dream since we were children to make amazing moments for motion pictures. It is a form of alchemy, and magic that we cannot easily ignore. We would likely do it if we were not paid (a lot of us did that just to get into the field, though I do prefer getting paid for it).

In the early 1990’s, there were few of us who knew how to make computer imagery, but that era is long past. It is now a global enterprise, and saying “no” to any job brings up a chance that a client will never call again, as they have found a new vendor for your services. Just like any other service industry — not much different than auto mechanics, plumbers, or electricians. So, goodbye sleep.

Thus, every time we push through the 3:00 A.M. wall, we must remind ourselves that what we do for a living is pretty interesting despite the challenge. Documentaries about VFX on television (now YouTube) show creative teams doing cool stuff, but do not directly depict the harsh realities of the job. The descriptions of the craft, especially in magazines of the late 1970’s to early 1980’s minimized the section about late-night work. Not that that really would have stopped anyone. For most of us, it is no longer just a hobby; Visual Effects is a career, it is hard work, and it is globally competitive. Budgets, technology, time, and sleep are the variables that shift around for any leg up on the competition, and it is tough to know where dedication and overwork cross paths. Sometimes it is not fun, but the result is still very cool.

Unfortunately, if you plan to be a visual effects artist, you probably have to get used to it. There are going to be late nights, missed meals, lost vacations, and at times you may forget what sleep feels like altogether.

You are not the first.

Where Did The Time Go?

Working long hours is not unique to our field. Benjamin Franklin in the 18th century was negotiating the French involvement in the American Revolution into the wee hours of the morning before electricity was used to light up that city (kind of ironic). Thomas Edison, as mentioned in an article by The Atlantic, later used that electricity to build long-lasting lightbulbs, but was a staunch opponent of sleep. The article points out that he would push his employees to work on as little as four hours of sleep, only hire those willing to embrace his insomnia, and begrudge those who could not keep up. He actually hired other sleepless people to assure employees were awake, and disliked any time they were in the throes of “unproductive sleep.”

One can assume long work hours have existed throughout history, they certainly have in VFX. L.B. Abbott recounts in his book Special Effects: Wire Tape and Rubber Band Style that his first day in the 1930’s as a VFX artist was 36 hours long — a pattern he learned to accept. One was expected to support the film no matter the personal cost. I am sure the employment situation during the depression had some contribution to that expectation.

In 2006 the VFX community started a fairly open discussion about working hours, and the rapidly declining schedules dictated by release dates. John Knoll broke the stoic industry-wide silence on the heels of the successful Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead Man’s Chest. He noted his only solution to the condensed schedule. “It just means there’s going to be a lot of overtime and weekend work,” he stated in an interview on movieWeb.com. Animation World News further reports:

Knoll continued [at a VES event] with a frank discussion about how the team’s short schedule on the second and third films made things very tough, and his strong dislike of short post schedules, and in fact said the schedule for these two films proved to be “the single hardest part” of doing the movies. It puts people in a situation where “Plan A has to work every time because there’s no time for Plan B” to be tried, Knoll said. He felt like it “might take a high profile disaster to change things,” by which he did not necessarily mean a missed delivery date but also a substandard final product, as tight schedules take not only a toll on the vfx team but all of the post production process.

Few people noticed, but Douglas Trumbull rolled his eyes during the next session at the VES festival over the subject. He insinuated that “Star Trek: The Motion Picture was pretty hard too.” In truth, the insanity of last minute delivery on STTMP is a thing of film legend, with music scored to blank leader (source: STTMP soundtrack liner notes), VFX extended in editing to fit slugs that could not be changed, and the last reel being flown in to the premiere just in time.

The 2015 book Return To Tomorrow, which chronicles the oral history of the making of STTMP, is a gut-pounding recount of the punishing work hours required of the film, due to decisions made far from the lives of those who had to actually create the images from scratch.

As Trumbull told Wolfram Hannemann of in70mm.com, “There were as many shots [in the movie] as “Close Encounters” and “Star Wars” combined … There were 650 shots, which had to be completed in six months … and we all worked 24 hours a day for six months. Seven days a week, around the clock, to get that movie done … I ended up in the hospital – it was a major recovery. I had ulcers, all kinds of exhaustion because I was working seven days a week, almost living in the studio, not getting enough sleep.”

STTMP in many ways became the model going forward for visual effects, with multiple vendors, insane work hours, and crushing deadlines. It was considered a hellish, cursed production at the time. An anomaly. It was more of a canary in a coal mine predicting the current VFX model, in which release dates are published long before any work has been done, and the deadline cannot be missed.

Unfortunately, working long hours remains the rule, as opposed to the unique circumstance. Knoll’s earlier point is that the decision makers above the artist are setting up impossible conditions, and the dedication to that promise is breaking on the backs of people’s lives. This intense work demand is not new, as it was common practice and encouraged in Thomas Edison’s day — but then again so was child labor in the United States at that time.

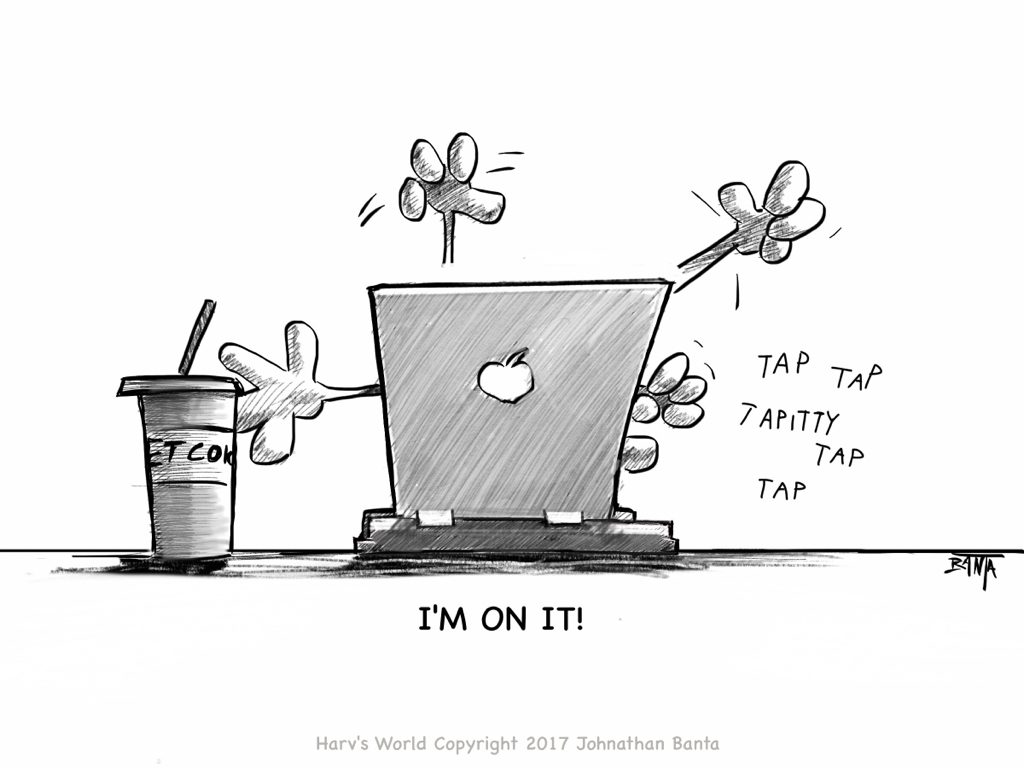

The cartoon above was drawn in 2017, by pure chance it matches a drawing from 2006 (below). It seems times have not changed very much.

The cartoon above was drawn in 2017, by pure chance it matches a drawing from 2006 (below). It seems times have not changed very much.

A Global Issue

So where is the industry now?

Standard practice in the VFX industry starts work at 10 hours a day (though an 8 hour day is better on budgets). Most people are happy for the extra work, and money it provides, but when the “crunch time” hits, overtime can quickly grow to 14 hours a day or more. In the current globalized economy, there is much more competition for capital than ever before, and at times VFX work around the world can resemble the sweat shops of the early twentieth century, which puts downward pressure on working conditions for everyone — especially considering overtime pay is not a universally accepted practice around the globe. The overtime hours often are part of the plan, because release dates and expanding visions (as well as a misguided concept of how VFX are made by some productions) have left little other choice. This results that people are often informed that they will be sacrificing their lives for this movie, that they will be working the weekend, or that lunch is being brought in so they can continue working — they are rarely asked.

By most accounts VFX artists are paid well for their work, when they are actually working, so little sympathy is expressed when they complain about their lack of sleep, or express exaggerations of sweatshop conditions (when there are actual VFX sweatshops in existence — don’t exaggerate about your circumstance). In emerging economies a large, nearly forced labor pool is common, and people who may be used to metaphorically “scratching a living out of the dirt” as it were, are happy to have a job. They are content to do it for less, and longer, as it is a leg up to a better life. The sweat shop purges of the 20th century in the United States have not yet taken hold in all parts of the globe, and the nineteenth century mindset of Edison is still in full swing — to some degree it is the natural progression of an emerging economy, and the response of a damaged one. How does one actually calculate the cost of sleep, anyway?

Employee rights vary per country, and globalized companies can easily take advantage of this — some may actually be doing so. For a global company it is not correct to enforce unrealistic conditions on one set of employees, and not the others. Facilities with global reach should enforce the highest standard among all their vendors or shops. In this manner they create a more dedicated workforce, and improve the conditions throughout the industry. It is bad enough that schedules are compressing, but exhausting the artist — the necessary cog in the equation — has only short term benefits. A dedicated, hard-working artist knowing their rights, and an employer knowing their legal limits can make a very effective team, and produce high quality work. It will not always be rosy, but the conditions are more conducive to positive results, and the 3:00 A.M. wall seems less onerous. The artists dedication is only protected if the artist is humbly aware of their skills, and enters into an equitable (and written) contract. In this way the employer receives a better product from the artist, who loves what they do, and sings the praises of the company. As a benefit, someone may actually get some sleep.

It sounds a bit utopian, and easier said than done. Can it hurt that much to try?

Why Am I here?

For an artist who is compensated by the hour, when a deadline is short, and the team needs to work as productively as possible, many go over hours — again this is often a choice of their own. Yet, If the company policy is “We only pay regular hours unless overtime is approved,” you must ask yourself why you are there? Are you approved, or do you have that much dedication, that your integrity is at stake if you cannot reach your deadline? Do you feel the need to pay for the privilege of working?

Day Rate employees are a whole different argument — who can benefit greatly, or acquire great abuse depending on the project. As for Sole-proprietors, working long hours is an issue with your boss (that would be you), and clear understanding of your strength and limitations in the flowing landscape of production.

A VFX production is a battle full of myriad challenges, and there is an Esprit de Corps that develops amongst a team. Sacrifice for the members of your team is honored and is occasionally a motivating factor. If your sacrifice is coerced by the employer, or is self-serving, it is in vain altogether, but if you feel compelled to work longer, and not get financially compensated for it, make that last mile benefit something more than your early demise. Build friendships and common experience, make your team the heroes, but find some alternate compensation that you feel is worthwhile.

Remember to ask yourself why you are there?

Get Over It, Kid?

Enough bellyaching, to be honest, what are we in VFX truly complaining about? Life is hard. Work is a struggle for everyone. Dad worked two jobs, and Grandpa worked three. Not sleeping because of work is not a new phenomenon. Maybe this is just what work is supposed to be, and we are all just whining brats. We complain too much, and need to realize how good we actually have it. There is an expectation of how we should act in these circumstances, and it is not necessarily antiquated: We are supposed to be strong enough to take it. We are expected to toughen up, and in truth we could use a little of that. It is not supposed to be a picnic with free money, but an opportunity to take pride in a fight well fought. Don’t cry about it.

At the same time, we should not accept abuse. There should be no reason for anyone to demand that you put all things aside at the end of a regular work day, and throw your life into chaos for a job. It is something you should be asked to do, and you choose to accept for the betterment of the job, and security of your position. An employer has a reasonable expectation of hard work for proper compensation, and an employee has the reasonable expectation that they will not be treated as slave labor. It is a contract, after all. There are likely consequences either way, and it is a struggle to know how to balance if a complaint is one of actual abuse, or our general tendency to want to take it easy.

Is it that we have fallen into a pattern and are walking over the cliff like lemmings? When is it too much, and when do we say “enough?” Worse yet, did we say it at the moment someone else volunteered, and pushed us aside? Are we being abused, complaining too much, or are we somehow abusing ourselves? So many questions remain hard to answer, even for a lemming.

Maybe we should just get used to the taste of Red Bull, 5-hour Energy, and Diet Coke.

Not Quite a Conclusion

When I was younger, I wore a generic button that said: “relax, its only a movie.” I purchased this button at Hells Half Acre in Wyoming in 1984, where Starship Troopers was eventually filmed in 1996. The next year, while shooting the film Pleasantville, a film crew member died driving off the road after a late day filming. Haskel Wexler made a documentary about the incident: Who Needs Sleep? It points out that this issue is bigger than just VFX. It is almost an epidemic. Yet, while film crews and actors complain about 19 hour days, I have seen nearly back-to-back 36 hour shifts. I have been on the road, barely getting home, and lying on the bed, every muscle spasming as my body collapsed into a deep sleep. (So much for that particular set of choices). I think back on the wisdom of that tiny generic button a lot.

I have recreated that button (if you want to buy one).

I recently heard an unidentified song that said: “I used to think time was of the essence, but now I just want to get some sleep.” Those are words to live by some days. It is a more competitive business than it has ever been, due to globalization. I am fairly certain the attack of the Z-Monster at the 3:00 am wall will visit me again. There is a certain amount of pride in being able to withstand the onslaught — but sleep deprivation for work in the film business is not a contest. It has, however, almost become the right of passage.

All this said, my record is 72 hours straight, with minutes to spare before the deadline. Tape delivered by me to the set for a live bluescreen shoot. 512 ounces of Diet Coke consumed. It was my first VFX gig. Beat that, suckers!

AG