Recollections of BOSS FILM STUDIOS

A recent post of one of my photos from Starship Troopers on social media erupted into a lengthy discussion about the BOSS Film work, some of which has heretofore received little mention. Following is a summary of that discussion, beefed up with a little bit of research from extant sources. You may have read some of these recollections previously, but I will endeavor to add more detail, to illustrate what it took to make visual effects almost twenty years ago, so please indulge me. Here goes:

It was rumored that Paul Verhoeven saw an image from the movie Turbulence, that BOSS had just finished, of a 747 ripping apart a parking garage, and asked “Why aren’t these people working on my film?” That image was a promotion still that I touched up from the film frame, specifically adding more detail to the blown-out explosion using stock elements by Peter Kuran at Visual Concept Engineering, which he sold commercially. This was just a rumor, but a fun one.

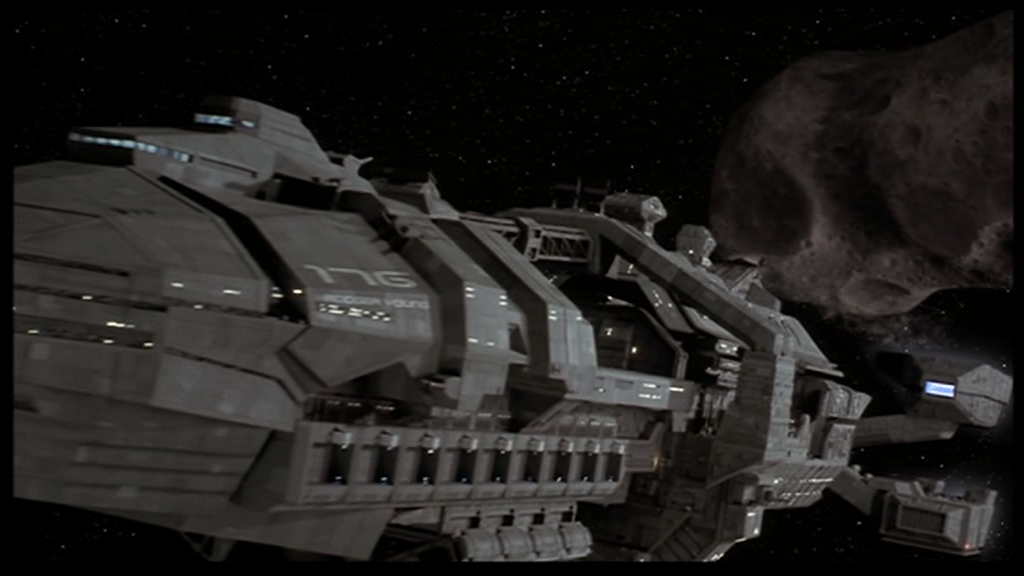

There were three teams producing spaceship sequence shots in Starship Troopers simultaneously: One at Sony, one at ILM, and the team at BOSS. Each of these facilities were given specific sections to produce, but because of the compressed schedule (BOSS was brought-in late to the production) there would be no asset exchange, since they were all busy in production. BOSS was responsible for the asteroid strike sequence, just AFTER the whipping of Johnny Rico in the film, and had several models on-stage.

Cinefex magazine says this about the BOSS work:

An additional twenty-four Rodger Young shots were farmed out to Boss Film Studios. In fact, Starship Troopers was the last feature assignment to be accepted by the esteemed facility before it closed its doors. “What we were working toward,” said Boss visual effects supervisor David Jones, “was the successful completion of two sequences involving the Rodger Young. The first featured a shot with an amazing camera move that begins out in space above the ship, dives down towards the miniature, abruptly tracks off at a ninety-degree angle, swings around, then moves in towards the bridge, with Carmen in the window — all in one shot.”

Boss achieved the dynamic camera move through the careful orchestration of disparate elements. Using molds from SPI, the company fashioned its own eighteen-foot miniature of the Rodger Young. “We then photographed the model motion control,” said Jones, “using a 24mm snorkel lens attached to the end of a boom arm for the dive down towards the Rodger Young and subsequent swing around to the front of the ship. That shot was then married up to a digital camera move, after the entire front end of our miniature was digitally replaced to make the ship’s bow section look more detailed. Finally, the digital section was match-moved to live-action footage of Carmen on the bridge set — footage captured with the camera on a swinging boom so that all the elements would match up.”

Boss complemented its motion control work with an overhead truss system. “Essentially it was a gravity-controlled model mover,” observed Jones, “a way of hanging a miniature from the ceiling much like a giant marionette, then motion controlling the wires to act in conjunction with our regular computer-controlled camera rigs. Two trusses were installed on stage for our effects scenes. They allowed us to make the Rodger Young model bank or turn, or rise up to twelve feet off the floor. The entire time, this enormous model was literally hanging from the ceiling.”

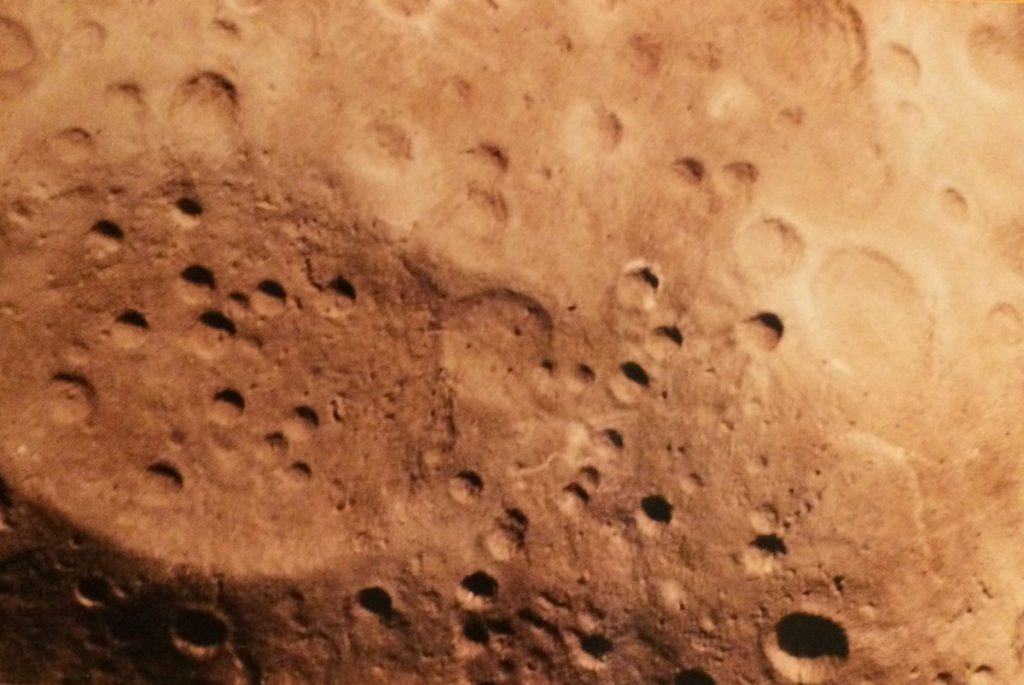

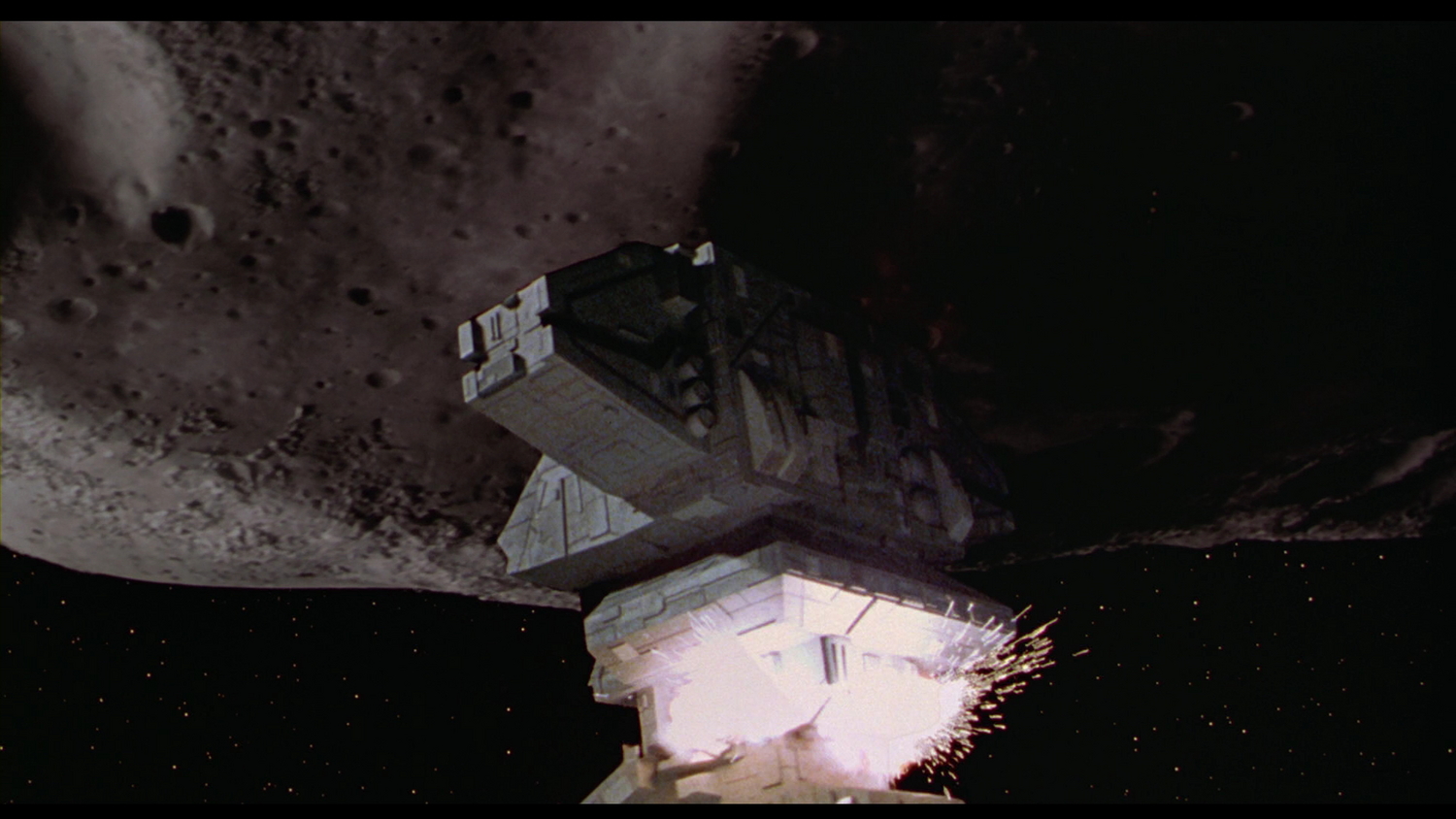

The truss was utilized for a second Boss sequence, in which the Rodger Young collides with a rogue asteroid the bugs have deflected towards earth. Computer controlled shots of the Boss Rodger Young model were composited with separately filmed footage featuring a highly detailed, eight-foot-long, Boss-built miniature of the asteroid, hung from the truss system and photographed against a tangerine-colored screen. For shots of the ship diving under the meteor, a separate, twenty-foot-long section of the asteroid was built, also photographed with the truss system. Subsequent shots of the asteroid actually clipping off the ship’s communications tower were achieved with a tower model that stood eight feet tall and eight feet wide and had a detachable upper section.

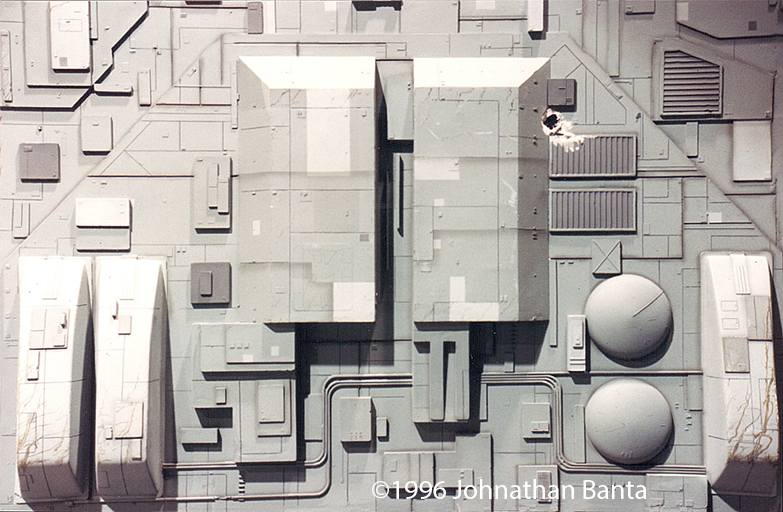

While at the facility I asked David Jones (Close Encounters, Star Wars, Galactica), the head of the model shop, why they had to build so many large sections of the model? He responded with “When you build miniatures too small, the specular reflection from the lights gives away its size, as does the scale of the material. By making them large, we get a better scale in the final shot.” Since the asteroid grazing sequence was so close to camera, large models were the order of the day. As an aside, David is known for putting R2D2 on all the models he builds as a signature homage. There is one on the Close Encounters ship, Air Force One, and surely the Rodger Young.

Many dedicated model builders were kept busy for months measuring the eighteen foot miniature with calipers, scaling that to paper patterns, and cutting or sculpting detail to match parts – that were at times kit-bashed parts from hobby model kits. I was a frequent visitor to the model shop, as I was responsible for matching the paint schemes and building graphics for the models on Air Force One. To make the process of scaling up the model more efficient, I proposed to one of the modelers that we take the object, which is rather flat, up to the xerox machine near the old matte painting department, and blow it up 400 percent. We could then take that resulting image and scale it another time to match the size they were reproducing. Since it was not my direct responsibility, I did get some heat for getting involved with the model shop — again. I was constantly trying to meld digital and practical methods to benefit of the model shop, so it was not the first time fingers were wagged at my involvement — at least it worked.

During my research, I found one of the models sold at auction by The Prop Store, who shares this detail:

This exploded tower piece consists of two, mounted sections that can be screen matched to the specific tower seen in the final film. Constructed primarily out of fiberglass, this piece also features sheet plastic detailing on the exterior portions, and metal and molded plastic details on the interior. The tower has been intricately painted, primarily in blue/grey shades, while the exploded portions are a darker, charred grey. Additionally, these two tower portions come mounted on a custom-made display with the film’s logo illuminated on the base. This piece is in good, production used condition.

Note the integrated pyrotechnics in the large section of the conning tower, as opposed to a digitally composited explosion, which is added on top.

The statement of The Prop Store is partially correct. This is from the Rodger Young model used in the film, but it is not the one pictured, as you can see by comparing the detail in the picture below with their model. However, the holes drilled in the surface are a direct indication it was used in the overhead marionette mounting system, and is therefore from the BOSS model shop.

VFXHQ reviewed the BOSS work on the sequence this way:

As the Rodger Young travels through space, an unexpected present is handed to them–an asteroid headed straight for them. With quick reflexes, the ship is able to avert the asteroid’s path with only minimal damage. The visual effects elements were created and shot by Boss Film Studios, and composited by POP Film.

The scene is quite different from just about every other space sequence in the film, in that only two major models populate space at any one time – the ship and the asteroid. As the asteroid slowly rotates toward the ship, its huge scale is accurately portrayed (due to its exceptional stage lighting), and the Rodger Young’s quick response to the asteroid is portrayed with an equal amount of interesting detail and believable choreography. Especially interesting is the subtle trail of debris that the RY trails into space. Especially awkward is the compositing of a particular explosion element when the asteroid hits the RY–the pyro element seemed completely unmotivated and out of scale.

The great deal of interior greenscreen compositing, even through violent camera shakes (especially one particular steadicam shot, when the captain appears on the bridge), is consistent and believable.

The sequence begins with a dramatic crane down, starting as a wide shot of the RY, and closing in on the cockpit of the craft. The shot is staggeringly complicated, with a portion of the model dissolving to a CG version, which is composited with the live-action footage. These transitions occur invisibly – the audience-at-large will never realize the various stages of this highly complicated shot. Unfortunately, the shot’s design is what makes it awkward–the movement of the camera is far too extreme, relative to the calm, almost sedate camera movements of other space shots, making the shot stick out and call attention to itself.

The zoom-in from space sequence utilized one of the most-detailed, full-frame CGI effects for its day. However, the entire shot is completely counter-intuitive to most VFX planners. One would expect that the small spacecraft, occupying no more than one-half of the screen would be a computer generated image, with a highly detailed miniature deftly composited to match the full-scale shot of the cockpit. The truth is it was photographed the opposite way. The eighteen-foot Rodger Young hung from its gantry at the end of a very large hangar in the Van Nuys airport (where they filmed Star Wars VFX). A motion control camera system on a very long track moved across the stage photographing the ship. at the mid-point, a CGI section of the craft was reproduced by scanning a piece of the Rodger Young pulled from the molds. This scanning model had red tape laid on it to guide the 3D scanning team — which used an encoded MicroScribe digitizing arm to create 3D coordinates (which I acquired at the end of business auction). Several photos of the model under various lighting conditions were used as a guide to the texture painting.

The zoom-in from space sequence utilized one of the most-detailed, full-frame CGI effects for its day. However, the entire shot is completely counter-intuitive to most VFX planners. One would expect that the small spacecraft, occupying no more than one-half of the screen would be a computer generated image, with a highly detailed miniature deftly composited to match the full-scale shot of the cockpit. The truth is it was photographed the opposite way. The eighteen-foot Rodger Young hung from its gantry at the end of a very large hangar in the Van Nuys airport (where they filmed Star Wars VFX). A motion control camera system on a very long track moved across the stage photographing the ship. at the mid-point, a CGI section of the craft was reproduced by scanning a piece of the Rodger Young pulled from the molds. This scanning model had red tape laid on it to guide the 3D scanning team — which used an encoded MicroScribe digitizing arm to create 3D coordinates (which I acquired at the end of business auction). Several photos of the model under various lighting conditions were used as a guide to the texture painting.  The final CGI was tracked to match both the miniature (using the motion control move as a start), and then tracked to the live action cockpit with BOSS’s proprietary 3D tracking system built by Maria Lando (chronicled in an earlier article). The front glass was a CGI construct as well.

The final CGI was tracked to match both the miniature (using the motion control move as a start), and then tracked to the live action cockpit with BOSS’s proprietary 3D tracking system built by Maria Lando (chronicled in an earlier article). The front glass was a CGI construct as well.

The miniatures were photographed in front of a tangerine screen, which was a recent innovation developed by Rob Legato and his team while filming Star Trek The Next Generation. It was consequently used on Apollo 13, and by BOSS films on Turbulence in 1996. Tangerine screens relied on the repeatability of motion control systems to shoot multiple passes of beauty, lighting, and mattes over a black-light illuminated screen. The tangerine screen produced a very flat background that was optically very easy to isolate, similar to the back-lit screens used on Star Wars, but was still shot double-pass. Unfortunately, the marionette rig was holding a significant amount of weight, and there were times that the matte passes did not perfectly line-up, and required digital manipulation to fit. There was no way to check if the pass worked on the day, as everything was shot on film (BOSS typically used 65mm film, but not sure in this case), and we would have to wait for dailies the next morning, and then wait for scanning from film. It was very slow.

Once elements were photographed, and scanned, each one would go through the imaging department. This department was responsible for balancing all of the scanned elements on color controlled Barco monitors, and building LUTs for the files that the compositors would apply — and never alter. This system was directly evolved from the old optical compositing days, and seems a little archaic now. Because of this separation of color control and compositing, based on old optical methods, often BOSS would have color imbalance of miniatures that would at times match the results of optical compositing. Any artist who modified the “God LUT” as it was referred to, would be lectured. This kind of control was necessary with film, but not so much digitally, and represents some of the growing pangs of digital Visual Effects.

Many of the tools and methods we take for granted these days were not available in 1997. One of those was camera-projection texture mapping, which was being pioneered at ILM and by Paul Debevec at the same time. Therefore, whatever CGI built for the scene needed to match the lighting of the miniature stage, and then shift to match the lighting of the full-size set. No small task, as we were still in the era of lighting with multiple point and distant lights, and global illumination, ambient occlusion, radiosity, and path tracing were either still theoretical, or computationally impossible. The rendering would be Pixar’s Renderman, with custom shaders written by the team. Camera projection of the live action plate would have helped to modify the original camera move, but it was not a standard technique yet, and not employed in this case.

Starship Troopers was being built at the same time Air Force One was attempting to finish. The SGI computer stations throughout the facility were slammed, and three expensive Inferno workstations were purchased to finish off that film, and transition on to Starship Troopers. Most of the compositing at the time was accomplished with Wavefront Composer 4.0, and 3D animation was put together with Wavefront animator — Maya did not yet exist. Special paint work to remove the wires which crossed across the very detailed model was a combination of Composer, Matador 64, and custom software written by Maria Lando. The paint work was fairly difficult, due to perspective changes in the model, and the intricate detail on the surface. Today that would have been handled by vector based warping, or camera projection, but in this case it was just a bunch of hard work.

Texturing the CGI model was the next step. BOSS used Amazon Paint 3D for most of its texture layout work — our technical support team were the Strauss brothers, who would later form their own VFX company and direct films. It had a very nice feature which allowed the artist to project a photo onto the surface, and it would extract the image to a flat texture based on the uv layout. It unfortunately had no way to store or transfer any camera information, so you would align it once, and that was it. I started trying to code a camera recorder for the software using their expression language, in conjunction with the filemaker database expert at BOSS, who had once worked on the computer code for the YF-23 stealth fighter prototype (he was seriously under-utilized). The plan was to use the photographs taken of the Rodger Young miniature, and map this on in this manner, apply those as patterns, using the same layer methodology I developed on Air Force One. However, that plan eventually changed, as many things did near this time.

I had previously resurrected the Macintosh computers for work on Turbulence, and Desperate Measures — computers which had been relegated to scanning and ad-hoc print design — for a lot of my photoshop work. I was on the matte painting, compositing, and texture painting team, and had a little experience with MacRenderman. I was adjusting shaders for Air Force One paint work, but the turnaround for test renders was days away. I started using Fractal Design Detailer, one of the early 3D texturing applications on Macintosh with rendering ability to test out texture layouts quickly. Because of this, and the heavy crunch on all the SGI computers (which I was no longer really working on), my producers asked me to develop a texturing pipeline that worked on Mac, and could be delivered to an outside vendor (Sassoon Film Design, my next employer) — who would create the textures for the CGI Rodger Young.

While waiting for the textures, and still working on Air Force One, I was asked to create lens flare elements for the engines as the spacecraft dove under the asteroid. In 1997 there were no lens flare plug-ins. Just a freeware tool that was written by John Knoll, that created the lens flares we are now all very familiar with. The lens flare elements were rendered in one pass by the tool, so I had to paint each one of the elements out into a layered photoshop document, and export each layer to its own file — which were then hand animated to the final shot in Composer. It is amazing to think so much work is so easily applied today.

While waiting for the textures, and still working on Air Force One, I was asked to create lens flare elements for the engines as the spacecraft dove under the asteroid. In 1997 there were no lens flare plug-ins. Just a freeware tool that was written by John Knoll, that created the lens flares we are now all very familiar with. The lens flare elements were rendered in one pass by the tool, so I had to paint each one of the elements out into a layered photoshop document, and export each layer to its own file — which were then hand animated to the final shot in Composer. It is amazing to think so much work is so easily applied today.

The large asteroid impact blew apart the conning tower of the Rodger Young, and it was photographed with several motion control passes, and miniature explosions. Particle systems were built in Wavefront Dynamation, and tracked to match the model move. Any interactive light would have been photographed on the miniature stage. Star field backgrounds were computer generated in RenderMan by Jim Rygiel. These were based on random and fractal distributions, but would change scale to compensate for motion blur — similar to ramping exposure on a camera, so that the star would not be lost during panning shots. These were composited behind all the spacecraft, asteroid, and outside the windows of the interior shots.

The large asteroid impact blew apart the conning tower of the Rodger Young, and it was photographed with several motion control passes, and miniature explosions. Particle systems were built in Wavefront Dynamation, and tracked to match the model move. Any interactive light would have been photographed on the miniature stage. Star field backgrounds were computer generated in RenderMan by Jim Rygiel. These were based on random and fractal distributions, but would change scale to compensate for motion blur — similar to ramping exposure on a camera, so that the star would not be lost during panning shots. These were composited behind all the spacecraft, asteroid, and outside the windows of the interior shots.

[Click the gallery above for some animated GIF]

The crushing workload at BOSS necessitated that interior shots be farmed out and composited by artists at Pacific Ocean Post, and then filmed out and sent back to BOSS for review, before being sent on to the client. Many of the biggest issues were the manner of composited reflections (use the ADD, SCREEN, or PLUS function, kiddies), and the look of out-of-focus stars (which they made their own artwork for). Star compositing was easily the biggest complaint from the clients, and generated multiple versions of shots — constantly being told that the ILM shots look a certain way (the tracking looks like it was only 2D, perhaps by hand). However, once approved shots from ILM showed up, all of the notes we had been applying would have failed those shots too. Welcome to Hollywood!

One final shot for the asteroid grazing sequence was a shot from the interior of the conning tower as it was ripped off. Twelve fellow space cadets were torn from their dining table, and thrown off through a matte painting into the inky blackness of space. Considering that Carmen and Zander were praised for their quick action (on a course she altered without permission), the filmmakers chose to move those shots later in the film for the destruction of the Rodger Young over Klendathu.

Into the Sunset

My contract was complete at the end of Air Force One, and I did not see the final results of the work until it premiered. I learned that the texture work was a good start, and that as resources opened up at BOSS, it was completed in the traditional pipeline, and the remaining texture artists who moved on in their career to become masters of the craft.

This look back is my best recollection of events almost twenty years ago, and I have tried to enhance that with records of the work made at the time. It is a more detailed look into what seems like stone-age technology, but it is also a teaching tool. I was able to witness a very narrow section of time in Visual Effects, where all the methods I had read about, and trained for, mixed together with an emerging, pervasive, and powerful medium. I learned tricks and techniques, along with ways of seeing and element deconstruction that I carry with me to this day.

AG

Hat Tip SciFi interfaces for imagery

and yourProps.com

A great gallery of all the Sony models

The word is spelled “hangar”, not “hanger”. The latter refers to anything that functions to “hang” something, while the former is a large building to house and protect aircraft.

The necessary single correction in all of these words has been made. I blame spell check. ;)

I don’t suppose you know what font was used on the computer interfaces?

Or what they used to make the starship’s yoke?